Revolution Rock

Jerry Renshaw - I use the pre-dawn hours to drink coffee, get caught up on cable news, and generally jump-start my nervous system. Two days before Christmas, a God-awful storm was beating Austin, and as I tried getting my brain in focus, I glanced up and saw the Fox News crawl move across the bottom of my TV screen, "Punk Singer Joe Strummer Dead at 50." Surely that couldn't be right; I waited 10 minutes for the headline to cycle back through again, and when it did, I sent off an early-morning e-mail that read, "Joe Strummer Dead," not knowing what else to say. I spent the whole wretched day wondering how in the hell it could be.

The Clash was the first punk band that could play their instruments and the first to articulate their fury in a coherent way. They steered clear of the Sex Pistols' scattershot nihilism, and the real-world focus of their politics was light-years ahead of later politico punks like the confused Crass. More importantly, the Clash was a great rock & roll band, above and beyond the roots music that informed their sound. Even the earliest Clash songs echoed reggae and rockabilly, with rough but well-crafted harmonies, a dead-solid rhythm section, and choruses like football chants. Shot through it all was the indignant yowl of Joe Strummer, full of passion and piss. Strummer's love of roots music grew throughout the band's life and blossomed in his association with the Pogues and later his own band, the Mescaleros.

It was so long ago that it's hard for under-30s to grasp how important the Clash was for so many people. More to the point, they brought their incendiary live show (watch Don Letts' Westway to the World DVD, whew!) to the U.S. and to Texas in particular, hanging out with Joe Ely and playing in cities ranging from Austin to Laredo. They may have been "Bored With the U.S.A.," but they sure loved Texas.

And it never happened again. No reunion shows, no comeback tours, no halfhearted attempts at rekindling it all. At least Sony Legacy had the sense to reissue the band's entire catalog, topping it off with 1999's fiery From Here to Eternity live CD (austinchronicle.com ).

Strom Thurmond, alive at 100. Joe Strummer, dead at 50. It's not fair.

-- Jerry Renshaw

Garageland

Tim Hambli - It was in the summer of 1975 that I first encountered Joe Strummer's pre-Clash band, the 101'ers. I was booking gigs for my college in London, and the 101'ers were booked for a private party one weekend. They had used the college's newly acquired P.A., and it was my job to check in all the equipment after any such event. On discovering that one of our six new Shure mics was missing -- subbed out for one held together with electrical tape -- it was my responsibility to either get it back or replace it.

After several fruitless attempts to contact Strummer at his squat in North London, I decided on a more direct approach. I knew the band had a regular Tuesday gig in a pub north of the Thames, so I went to one of their shows to exchange mics. Waiting for a break between sets, I jumped onstage and made the swap. This went a lot smoother than I expected; the band had gone for beers, and nobody seemed concerned about my actions.

Mission accomplished, and feeling pretty pleased with myself, I stayed for a couple of pints. To this day, it's hard to describe my reactions to seeing Strummer play. I had never before seen such intensity and such unrestrained energy in a lead singer. At that time, their music was generically termed "pub rock." I remember the Chuck Berry covers at 90 mph, with Strummer literally spitting out the lyrics as the veins in his neck and forehead looked like they were about to burst. He could barely carry a tune, but that didn't matter. His performance was mesmerizing.

Despite my reason for being there, I was so impressed that I booked them for a Friday night gig at the student union that October. They weren't exactly a huge draw, with about 35 punters paying 30 pence (approximately 50 cents), but in my mind, the gig was a huge success; the whole audience danced like lunatics, and the band got at least three encores. As word of this event spread, I got more and more requests to rebook the band, so on March 26, 1976, they played the student union again. This time, the sold-out crowd went nuts for the whole show. The band was happy (they'd been paid 125 pounds) and didn't even try to leave with any of our P.A. equipment.

This was just the beginning of the punk movement. The 101'ers were like the missing link that connected pub rock to punk rock. I had already turned down a free gig from a guy called Malcolm McLaren, who wanted his band the Sex Pistols to get exposure at some smaller college venues. As their first gigs had already garnered a fair bit of publicity, I decided that booking a band that taunted, spat on, and picked fights with the audience was not my idea of a good gig. It still isn't.

At the end of that summer, I went into the Voluntary Service Overseas, the British equivalent of the Peace Corps. I spent two years in the Caribbean on the island of Dominica, where my only connection with the music scene was a subscription to NME. On my return to England, much had changed. Long hair was now very uncool, punk had transformed the fashion and music scene, and the Clash was one of the most popular bands in the country. Strummer's interest in dub and reggae had been absorbed into the band's music, and his lyrics had created a much-needed awareness of politics and racism in Margaret Thatcher's conservative government.

I remember my cousin from California visiting me in London sometime later. Wanting to give him the complete "British experience," I got tickets to see the Clash at Hammersmith. It was incredible. The audience was a throbbing mass, with the hard-core crowd at the front of the stage spitting into the air throughout the show. This created a haze of phlegm through which most of the audience viewed the band. This aggravated Strummer, and he told them so, but it didn't impair his performance, which was electrifying. I left feeling exhilarated. My cousin left speechless.

-- Tim Hamblin

Lubbock Calling

Raoul Hernandez - "I think it was '78 when we went over to London to tour," recalls Joe Ely. "We were playing this place called the Venue, and these scraggly looking guys were backstage talking to us. They told us, 'We have a band here in London,' and that they really liked the record we had out. I think it was Honky Tonk Masquerade; we'd had big success on our first three records there. So we said, 'Oh yeah, great. Thanks,' and they told us their band name. 'Course in '78, we were coming straight from Lubbock [laughs]. We'd never heard of the Clash. We didn't know anything that was going on in London. Hell, none of us even had a telephone.

"But they were great guys, and they invited us out after the show for a beer. They knew the town, and everybody knew them. They took us to all these places, then they invited us down to the studio where they were recording. Since we were around London for the whole week, we saw them quite a few times.

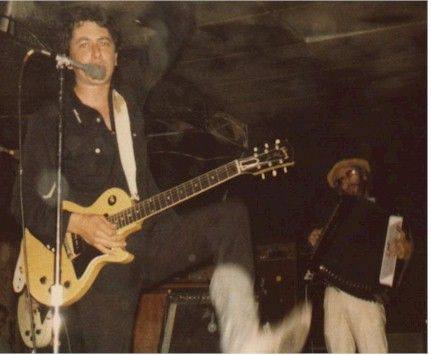

Jones, Strummer, and Simonon at the Armadillo (Photo By Ken Hoge)

"We said, 'Well, if you ever get over across the ocean, look us up. We'll take you to some good places in Texas.' They were really fascinated with Texas, and especially towns with names like Laredo, El Paso, San Antonio. To them, Texas was a mythical place that they only knew about in old Marty Robbins gunfighter ballads and Westerns and stuff.

"They said, 'Yeah, sure,' but we didn't really expect anything of it. We get back to Lubbock, and I get a call from our booker. They'd gotten a call from London: Some band they'd never heard of was coming to America and wanted to do some shows with us. They were coming to Texas. I said. 'Yeah, that's the Clash. Let's bring 'em to Lubbock.' They didn't want to play the big cities, they wanted to play the little towns in Texas. That was right after the Sex Pistols had played San Antonio, and it had become huge news because there was a near-riot. So the Clash wanted to go to, like, Wichita Falls, Lubbock, Laredo, El Paso.

"They spent several days in Lubbock, and I showed them Buddy Holly's grave. I don't think anybody in Lubbock had ever heard of the Clash, but our band drew, so we packed the place. We played first, and the Clash closed. Everybody was scared to death at first, but by the end, the dance floor was full. In Lubbock, that's how you know if people are digging it -- if the dance floor's full. At the end of the set, we did some stuff together, 'Not Fade Away' and maybe 'Peggy Sue.' They were doing 'I Fought the Law,' which was Sonny Curtis. They were huge fans of [Crickett] Sonny Curtis and knew he was from Lubbock, too. ...

"We went back to London in 1980 and did their whole London Calling tour. That was the time that was the most amazing, me seeing the Clash in their own environment. The first show was at a place called the Electric Ballroom in Camden Town, and it was the m-o-s-t amazing show I've ever seen. You couldn't hardly see the band, because the crowd was so hot they made a cloud. It was a cold night, and there was an actual cloud inside the room that came down over the tops of people's heads. People were looking up through the fog at this show, and it was a-mazing. I've never seen anything like that."

-- Raoul Hernandez

All the Young Punks

Jesse Sublett - In June 1979, the same week John Wayne died, the late Jeff Whittington started off his weekly column in The Daily Texan with a list of groups that would be competing in Raul's Battle of the Bands. Top prize was $300 and an opening slot for the Clash at Armadillo World Headquarters.

Unfortunately, Jeff erroneously included the name of my band, the Skunks. The following week he wrote a retraction:

Strummer and Ely (kneeling) backstage at the Dillo (Photo By Ken Hoge)

The Skunks will not be playing in the upcoming Raul's Battle of the Bands. According to bass person Jesse Sublett, "Billy Blackmon said, 'No,' Jon Dee Graham said, 'We are disqualifying ourselves,' and I say, 'Why would we want to open for the Clash? Don't you think the Clash would think a New Wave Battle of the Bands is a quaint idea?'"

I was cocky then.

The Skunks were one of the top draws in Austin in those days. We'd rocked CBGB and other hip meccas in NYC. And truthfully, I wasn't a big Clash fan. After hearing Give 'Em Enough Rope and the Cost of Living EP, I saw the light. Contrasted with the Sex Pistols' fuck-everything ethos, the Clash actually had heart and soul and roots. They rocked just as hard (maybe), and they were a left-wing buzz saw during the Reagan/Thatcher era.

Who remembers who won that battle of the bands? Ironically, the Armadillo gave the Skunks the opening slot anyway. They liked us, and on shows like these, they depended on the Skunks to help fill the house; although with Joe Ely in the middle slot, it probably wasn't necessary. That night our set went over like gangbusters. Ely got the house swinging with his soaring Lubbock band, then the Clash blowtorched the place.

They were a whirlwind, a force of nature, the loudest band I'd ever seen at the 'Dillo. The night was already unforgettable, but afterward the Skunks had a gig at the Continental Club. Concert overflow and rumors packed the joint quickly. In the middle of our first set, Mick Jones, Topper Headon, and Joe Ely wanted to jam. We fixed them up with guitars and launched into Ely's "Fingernails." The crowd roared.

Jones and Strummer (front center) at "Buddy Holly High." (Photo By Joe Ely)

Afterward, I led them in "Route 66," "You Keep a Knockin'," plus some Kinks and Stones covers. Mick Jones was fabulous at slashing out three chord anthems, while Topper Headon bashed hard. Ely played with his usual ferocity. Jon Dee and I kicked our usual overdrive upward several notches. Anyone who was there could tell you, it was the kind of night that rekindles your faith in the power of rock & roll. The music was hot enough to blow the hat off a die-hard cosmic cowboy.

In fact, one guy in the audience that night was Roger One Knight, an old Austin hand, a stalwart friend of Willie who never went anywhere without his cowboy hat and was skeptical of all this "New Wave/punk stuff." The day after the Continental jam, Roger got a cool haircut and started leaving that Stetson at home.

-- Jesse Sublett

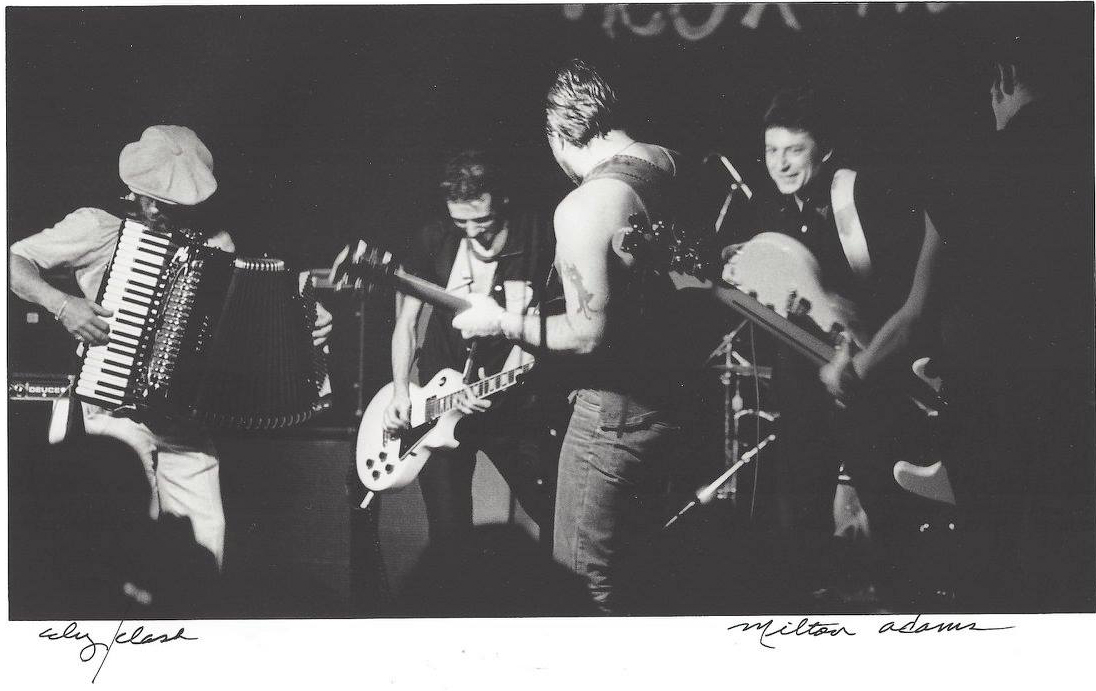

Four Horsemen

By the time Joe Ely and his frontline of Jesse Taylor, Smoky Joe Miller, Ponty Bone, and Lloyd Maines got through dousing sonic gasoline all over the Armadillo stage, it only took one musical match from the Clash to burn down the house. In almost 10 years of going to shows at the former roller rink, this might have been the finest ever. Austin was so hungry for true punk, it seemed like a foregone conclusion that this might be the show of 1979. It was even better.

Combining the ferocious combustion of drummer Nicky "Topper" Headon -- the secret hero of the band -- and bassist Paul Simonon with the fervent antics of singers Joe Strummer and Mick Jones, the Clash was the most exciting group in the world at that moment. Songs like "White Riot" and "I'm So Bored With the U.S.A." came across as religious screeds, turning the band's concerts into holy rock & roller tent revival gatherings.

Rock the Coliseum: Strummer (Photo By Martha Grenon)

Bill Bentley - The most impressive surprise about the night was how strongly the band played. So much of punk is based on nonmusical assaults that watching this quartet work its muscular magic was nothing short of mind-bending. Then, just about the time it seemed like there was absolutely no way for the quartet to top itself, they pulled out brand-new songs like "London Calling," "Wrong 'Em Boyo," and "Clampdown" with a dazzling swagger to suggest we hadn't seen nothing yet.

The concert really felt like one of those wonderful Fourth of July fireworks shows where each night-sky blast is more breathtaking than the last. In a tip of the hat to Texas, the Bobby Fuller Four's "I Fought the Law" finished everyone off with a neutron bomb intensity that left most of the audience gasping for breath and those who could still walk heading for the Continental Club.

-- Bill Bentley

Rock the Capital

Chris Layton - "It was traumatic," recalls Chris Layton about Double Trouble's first-night opening slot for the Clash at the City Coliseum in 1982. "We were warned that the Clash's audience hated everyone, but we figured, 'Hey, this is good ol' liberal Austin!'"

Indeed, watching rising star Stevie Ray Vaughan being heckled mercilessly on the Combat Rock tour was depressing and embarrassing, but it was a bad move from the start to book the local blues trio. The Clash cultivated a punk audience who valued passion over precision, and Double Trouble was too slick for their raw standards.

Mr. Smarty Pants' Clash Chronicle cover from 1981 (Photo By R.U. Steinberg)

The Clash rolled into town early to scout opening bands. It was their m.o., a move that won them much respect. The day before the show, management representative Stuart Weintraub sat at the Sheraton Hotel and fielded tapes from local bands vying for the opener -- D-Day, the Lift, 5 Spot. That night, the Clash were scoping out reggae bands, dropping by the Opera House to catch Stevie, and sweeping into the Continental Club to see a rockabilly outfit called the Trouble Boys. Double Trouble got the now-infamous gig that began as badly as it ended.

"To walk out into the lights and see people throwing shit at us and shooting us the rod, yelling 'get fucked' and 'get off the stage' was awful," remembers Layton. "At Montreux, there were four or five people booing, and it felt like 400 or 500. I remember [the Coliseum] as being venomous. Stevie was like, 'What is all this shit?'

"Afterward, Stevie thanked Joe [Strummer] and said, 'I guess I don't understand your audience. We're not accustomed to this, and we can't do tomorrow night.' Strummer was real apologetic, a great guy. But I'm surprised they found anyone to open [the second night]."

Alice Berry faced the same atmosphere with decidedly different results.

"I was standing backstage after Double Trouble's sad departure," explains Berry. "Stuart Weintraub turned to me and said, 'So, what are you doing tomorrow night?' -- like maybe asking for a date. 'Seeing the Clash?' I answered. 'How'd you like to open for them?' he asked."

-- Chris Layton

Jonesy

A five-piece rockabilly outfit with a chick singer, the Trouble Boys featured Berry and possessed what SRV did not: street cred in the punk community. The Trouble Boys were untried, unrecorded, unheralded, and unknown, perfect candidates for an audience for whom throwing beer cups and spitting meant "we love you" as often as it meant "fuck off."

"I have a vivid memory of this fellow shooting the bird at me," laughs Berry. "I decided to 'make love' to him from the stage, doing Patsy Cline's 'Walkin' After Midnight' with as much gushy ooze as I could muster. At the end, he was just smiling, and I felt we did our job. Nobody hit me with a beer cup or can. No one gobbed me. Just a guy shooting the bird."

Opening bands weren't the only political tune being played on Clash's Combat Rock shows in Austin. "Clash = Cash" screamed one of the hand-scrawled anti-Clash posters, as some of the band's fans felt they had deviated from their revolutionary form. Neither as groundbreaking as the earlier Armadillo show nor as MOR as their accompanying show at San Antonio's Majestic Theatre, the Coliseum shows were full-bore Clash. They stormed the stage both nights energized by their increasing success and making a place in local lore by filming the "Rock the Casbah" video in Austin.

SRV and Double Trouble took the lesson on the chin, going on to platinum fame. The Trouble Boys had a brief run and broke up within a year. As for all the Clash audience's attitude, the highly successful Combat Rock marked the beginning of the end.

-- Margaret Moser

Career Opportunities

Terri Lord - I have never worn a Clash T-shirt. No Clash poster has adorned my walls. I did, however, possess a Clash battery-operated clock once, constructed by myself, commemorating the first time that Mick Jones and Joe Strummer appeared on the cover of Rolling Stone.

The clock existed for many reasons. Certainly, in my circle, the regard for their music was worshipful. In fact, an earlier band I had been in had shunned their guitar tuners, preferring instead to tune to the opening chord of "Tommy Gun" (a perfect "E") before our shows. Joe and Mick were the punk rock Lennon/McCartney, and with their newfound status as Rolling Stone cover boys, they were in a position to be the punk rock ambassadors to the world. This was, of course, secondary to the fact that Mick looked really cute in the photo.

It was 1982, and Margaret Moser, Austin Chronicle music columnist and scenestress supreme, called to let me know that the band was coming to town a day early to shoot a video. I'd never been on Margaret's "will call" list, but in this case she was privy to a piece of information she thought I might find useful. The Clash's concert had sold out so quickly that the band had decided to add a second night and were looking for an opening band.

She suggested I go to the Continental Club that night and give a cassette of my band the Jitters to their manager, Kosmo Vinyl. When I got to the club, it was obvious that the word had spread, since the place was crawling with other hopefuls. I'd just given my tape to a very disinterested Kosmo when the Clash's road manager struck up a conversation with me.

Hearing I was a drummer, he introduced me to the band's drummer, also named Terry. At some point, I realized that Mick, in a big Panama hat, had joined us and was smiling at me. Yes, my heart stopped. Having had, as a 10-year-old, an entire wall papered with Bobby Sherman posters, this was the perfect culmination of all my post-post-adolescent fantasies. We talked for a good while. He seemed pretty interested in the clock, though I tried to gloss over the specific placement of the actual timepiece in proportion to his crotch in the photo.

After the concert the next night, having been given a backstage pass by Margaret after being sequestered in a room with her and two members of the Standing Waves, I found myself sitting in a row of empty chairs directly behind the stage. Gradually, the chairs began to fill with beautiful women that I recognized from the scene. Could they be the legendary Texas Blondes? Several of them gave me critically assessing glances so withering I felt obligated to assure them that we were not there for the same thing. Sure, I found Mick compelling, but I would never go up against a Texas Blonde and kid myself that I would get the guy. I had no spike heels. I had no miniskirt. I was there for my band, and truth be told, I found some of the Blondes to be as compelling as Mick.

Eventually, they opened up the huge backstage area, and everyone milled around, mingling with the crew till the band came out. Mick told me that there were two vans, one of which was going to Malibu Raceway, and did I have any other entertainment suggestions for the evening? I remembered that reggae band the Twinkle Brothers were playing that night, so Mick, Terry, and Karla, the singer from Toxic Shock, along with assorted crew members, all piled in the other van and headed over to Liberty Lunch.

Brazen American woman that I am, I offered to buy Mick a drink. Vodka and orange. He asked if there was anything else going on that night. If he was trying to pick me up, I sure wasn't getting it. I mentioned that Charlie Sexton was playing at the AusTex Lounge, so the whole group went there and had drinks till it was decided that it was time to return to the Sheraton Crest.

As we entered the lobby, Karla and Terry and the rest walked to the left toward the bar while Mick and I walked to the right, toward the elevator. My moment of truth and realization came as the elevator doors began to close, and Karla looked back at me in wonderment. That's what remains in my memory most indelibly -- her face as the elevator door closed.

What went on that night is probably what goes on in most hotel rooms. There was some of that, and there was some political discussion. There was some channel surfing for news of England, which had just invaded the Falklands. One thing we didn't discuss was my band. Whether the opening slot for the next night had already been decided I'll never know. Call me naive, but I didn't think to bring it up. Once I got the opportunity to actually spend the night with him, I don't think I even remembered I was in a band. Given the choice between "career" and "heart," I saw his puppy-dog eyes and chose the latter. Some feminist.

Yet it was truly like something from a dream. He shyly mentioned that the next night he'd like to see what I looked like in a dress. My subconscious had a hearty laugh at that since I only owned one dress, and I didn't think Mick would enjoy seeing me in my Flying Nun Halloween costume. Suffice it to say that I was wearing my leather jacket and black jeans the next time he saw me, and save for a smile from the stage, he paid me absolutely no attention. I guess his interest in politics didn't extend to the sexual. Then again, I wasn't all that informed about the government dole and the guns of Brixton. I think that we both got what we wanted out of the situation.

The clock battery ran down, and I never replaced it. I guess I didn't need to.

-- Terri Lord

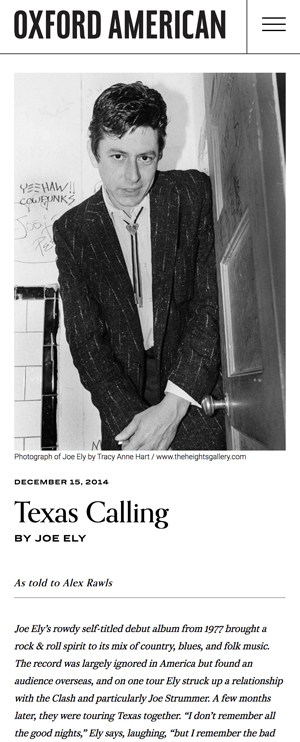

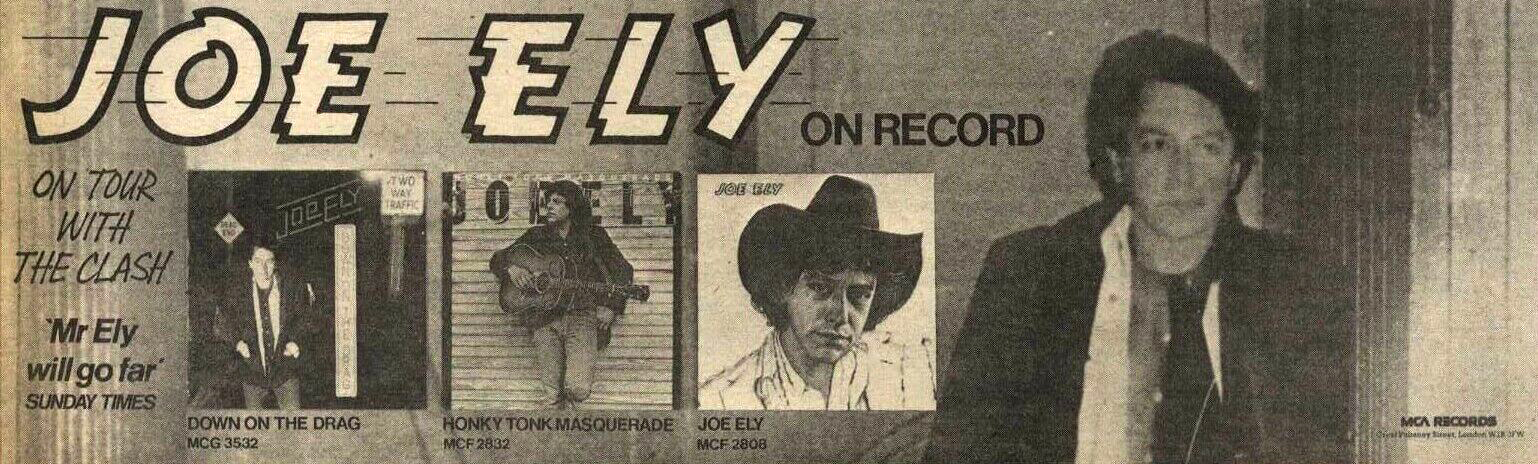

Joe Ely’s rowdy self-titled debut album from 1977 brought a rock & roll spirit to its mix of country, blues, and folk music. The record was largely ignored in America but found an audience overseas, and on one tour Ely struck up a relationship with the Clash and particularly Joe Strummer. A few months later, they were touring Texas together. “I don’t remember all the good nights,” Ely says, laughing, “but I remember the bad nights really well.”

Joe Ely’s rowdy self-titled debut album from 1977 brought a rock & roll spirit to its mix of country, blues, and folk music. The record was largely ignored in America but found an audience overseas, and on one tour Ely struck up a relationship with the Clash and particularly Joe Strummer. A few months later, they were touring Texas together. “I don’t remember all the good nights,” Ely says, laughing, “but I remember the bad nights really well.”

No known audio or video

No known audio or video

%20Storm%20the%20Palladium%20in%20'79/For%20Your%20Weekend%20Listening%20Pleasure_%20The%20Clash%20(and%20Joe%20Ely)%20Storm%20the%20Palladium%20in%20'79%20_%20Unfair%20Park%20_%20Dallas%20_%20Dallas%20Observer%20_%20The%20Leading%20Independent%20News%20Source%20in%20Dallas,%20Texas-300.jpg)

The Official Clash

The Official Clash  Clash City Snappers

Clash City Snappers