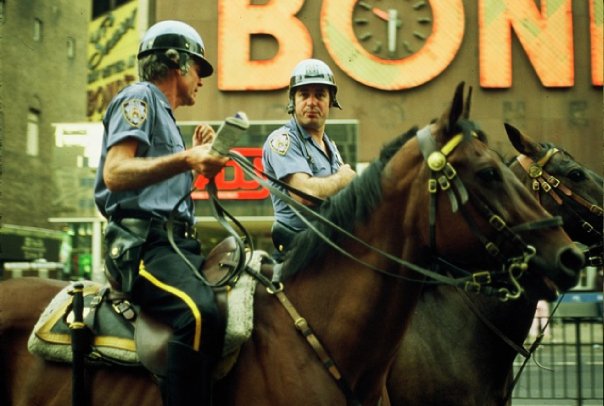

BOND'S INTERNATIONAL CASINO--

1530 Broadway, on the east side of Broadway between 44th and 45th Streets. (Often spelled without an apostrophe.)

A short-lived discotheque most famous for hosting the "Clash on Broadway" residency in 1981, Bond's sat on one of the Times Square-iest spots of land in Times Square.

Location

1530 Broadway (between 44th & 45th Street) New York City

Active years:

July 1980 - ???

DeeJays:

Raul Rodriguez, John Ceglia, Kenny Carpenter, Bert Bevans

Steve Mack

Facts

— owners John Addison & Maurice Brahms, later Mike Stone

— the place had previously been Bond's Men's Clothing Store

— owners put in over 1.5 million dollars in the place

— enormous club - 9000 square feet of open space

— the main dancefloor could hold some 3000 people

— there was a second dancefloor downstairs and 5-6 VIP rooms upstairs - each in size of a normal todays club

— it was reputed to be the world's largest disco

— the sound system was designed by Richard Long, who also did the Paradise Garage

— Bond's was originally more of a Punk/Rock Club but by late 1981 dance music ruled

— crowd was a mixture of black and white, staight and gay

— UK Punk rockers, the Clash, filled the club several nights in a row in 1981, this also led to a fans riot at Times Square

— today it's some kind of diner/teathre called Bonds 45, but you can still see BONDS written on the brick wall in 44th Street

History

The Bow-Ties that Bond BOND'S INTERNATIONAL CASINO--1530 Broadway, on the east side of Broadway between 44th and 45th Streets. (Often spelled without an apostrophe.) A short-lived discotheque most famous for hosting the "Clash on Broadway" residency in 1981, Bond's sat on one of the Times Squareiest spots of land in Times Square.

This New York Times article summarizes its phases well, but I'll add some elaboration here, as is my wont. Before the Times set up shop in the area, Longacre Square was the horse dung-scented center of New York's carriage trade.

An unseemly spot indeed for the future Crossroads of the World, but as the city's entertainment districts had been inexorably migrating ever further uptown along Broadway throughout the 19th century, the Square's eventual colonization by the theater crowd was inevitable. Oscar Hammerstein I was the earliest impresario to venture there.

In 1895, on the site of the former 71st Regiment Armory (destroyed in a fire), he opened the Olympia Theatre, a massive Beaux Arts complex comprising a 2,800-seat Music Hall, a 1,850- seat playhouse called the Lyric Theatre, a smaller Concert Hall, and a roof garden theater. According to Anthony Bianco's Ghosts of 42nd Street (New York: HarperCollins, 2004), admission was fifty cents, and patrons could wander between the theaters at will. "[T]he Olympia did not style itself as a family entertainment venue," writes Bianco. "Content to leave the middle of the road to others, Hammerstein experimented with provocative new acts and formats that expanded vaudeville's boundaries."

Hammerstein's adventurous fare included operas (some of which were his own compositions), "Living Pictures" (tableaus presented partially in the nude), Isham's Octaroons (an African-American song-and-dance troupe), and a notoriously so-bad-they're-good act called the Cherry Sisters.

Unfortunately, not every production he put on was a financial success, which led to a foreclosure on the property after only three years of operation. The building was auctioned off, and the theaters became separate entities under the auspices of different producers. Hammerstein's next local enterprises, the smaller-in-scale Victoria and Republic Theatres, were more lucrative. Meanwhile, the Music Hall was renamed the New York Theater, and was converted into a movie/vaudeville house when Loew's took it over in 1915. The Lyric was renamed the Criterion, and also became a movie house in the '20s. In 1907 Flo Ziegfeld staged his first production of Follies at the rooftop garden theater, renamed Le Jardin de Paris. When he decamped for the New Amsterdam in 1913, the roof garden was converted into a dancehall called Jardin des Danses. Despite its many virtues, the magnificent Olympia building did not outlast the Depression; it was demolished in 1935.

A year later, the Criterion Building rose in its stead. It occupied the same

block-long frontage, but was not nearly as tall as its predecessor--unless

you include the height of its huge rooftop neon sign, a fish-festooned

spectacular advertising Wrigley's Spearmint Gum. The building featured a

new Criterion movie house (designed by Thomas Lamb and Eugene de

Rosa), ground-level retail space, and a fabulous Art Deco

nightclub/restaurant called the International Casino. According to Susan

Waggoner's Nightclub Nights: Art, Legend, and Style, 1920-1960 (New

York: Rizzoli, 2001), this Casino had nothing to do with gambling:

Once one passed through the solid brass doors and into the red and gold

mosaic lobby, there was no shortage of amusements. The Cosmopolitan

Salon was fitted with a small stage and littered with settees that could

accommodate nearly eight hundred. Another one hundred and sixty could

quench their thirst at the Spiral Bar, a curved slide of polished mahogany

that swept from the ground floor up to the mezzanine. All this was a mere

warm-up for the main room, where tiered platforms assured all fifteen

hundred diners an unobstructed view of the show.

The show, mounted on an elaborately high-tech motorized stage, featured

such delights as "novelties from five continents and the beauties of ten

countries," an orchestra "whose reed section might suddenly plunge from

sight, like riders on a parachute drop," a fanciful "Ice Frolics" revue,

comedians like Milton Berle, and gorgeous chorus gals with gams for days.

The swank Streamline Moderne surroundings were "designed by Donald

Deckie, who later designed the Radio City Music Hall," according to Anthony

Haden-Guest's The Last Party (New York: William Morrow, 1997). However,

the Casino may have been too gloriously grandiose for its own good; much

like the Olympia, it closed after a mere three years in business.

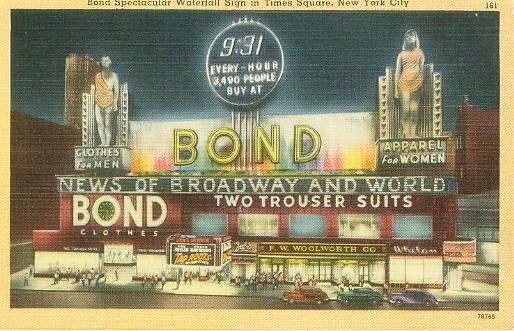

Bond Clothes took over the Casino's space in 1940, styling itself as the

world's largest men's haberdashery, and offering some women's wear as

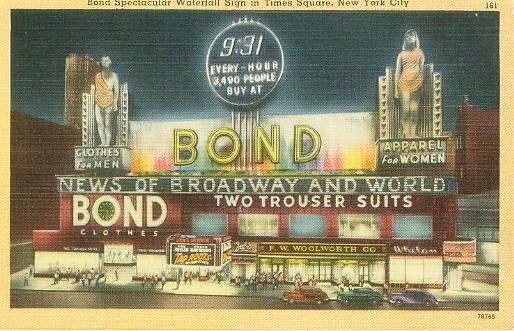

well. As if the store's famous "TWO TROUSER SUITS" neon sign weren't

enough, beginning in 1948 it also boasted the most splendid spectacular

ever to grace the Great White Way, designed by Douglas Leigh for Artkraft-

Strauss. As described in Leigh's 1999 Times obituary:

At the base of the Bond sign was an electric news zipper, about five feet

high, running along the entire facade. In Mr. Leigh's design, twin 50-foothigh

figures, one male and one female, flanked a waterfall 27 feet high and

120 feet long. Strands of electric lights seemed to clothe the chunky

classical figures at night, but by day they appeared naked.

Those loincloth-lights were added only after guests at the Hotel Astor

across the street complained about the statues' scandalously starkers state.

A clock poised above the waterfall perpetually reminded the public, "EVERY

HOUR 3,490 PEOPLE BUY AT BOND." (I suppose an even 3,500 customers

per hour would have been too much to handle...)

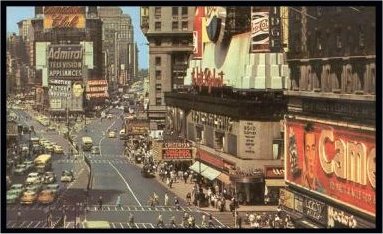

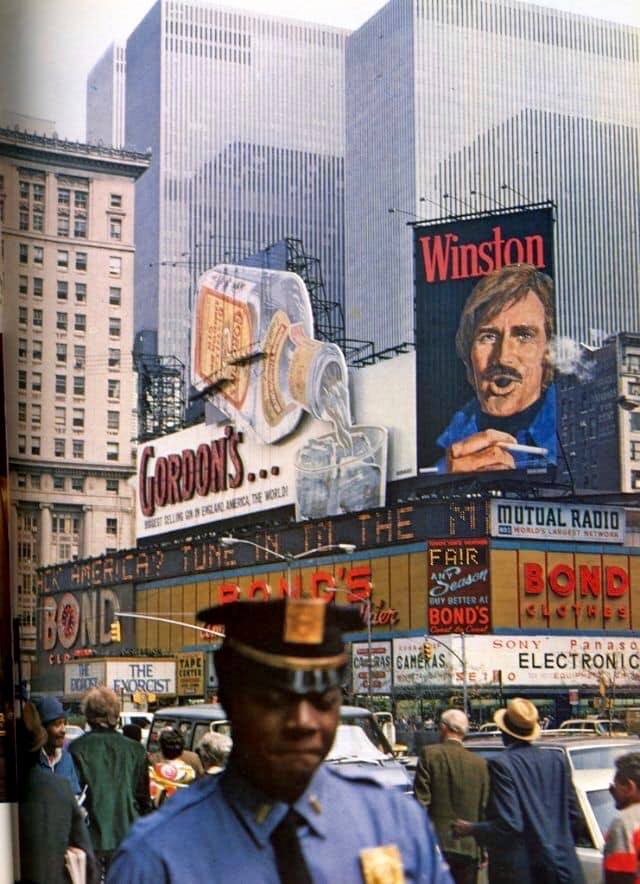

After six good-looking years, the sign was replaced with a Pepsi ad; the

waterfall remained (and kept gushing until the early '60s), but was now

flanked with giant Pepsi bottles. Apparently a Chevy ad was once meant to

take Pepsi's place, but a garagantuan Gordon's Gin bottle and a smoking

Winston man (a total Camel sign rip-off) eventually appeared there instead.

The ground-level storefronts evolved over time as well--among the

successive occupants were Woolworth's, Whelan Drugs, King of Slim's Ties,

Loft's Candy, Regal Shoes, Disc-O-Mat Records, tourist tchotchke outlets,

and those ubiquitous bad-deal '70s/'80s electronics stores.

Bond Clothes sold its last two-trouser suit in 1977, and after a couple of

vacant years, the space was respectfully rechristened as Bond's

International Casino, supposedly the largest disco the world had yet seen.

As described in The Last Party, the club was co-owned by John Addison and

Maurice Brahms. It opened in July 1980, and featured such accoutrements

as a "musical staircase," fountains retrieved from the set of The Liberace

Show (which often ended up filled with near-naked patrons), and a wideranging

music policy (usually spun by resident DJ Kenny Carpenter).

However, according to these opinionated folks on discomusic.com, the joint

never quite caught on, for various reasons--bad location (Times Square at

the height of its sleazy-seedy era), poor acoustics, lack of an atmospheric

theme, inconsisent musical choices, and above all, too much space to fill on

a nightly basis.

There were no such space-filling difficulties during the Clash's booking in

May-June, 1981. The buzz surrounding their initial eight-night stand was so

high that the shows were dangerously oversold--3,500 tickets for each

night, at a venue with a legal capacity of about 1,800. The FDNY

threatened to shut the place down following the first two overcrowded

nights. After much negotiation with city authorities, the band worked out a

deal wherein they would play as many shows as it would take to honor all

ticket holders--an unprecedented seventeen concerts. Times Square hadn't

seen that much commotion since Frankie at the Paramount, or V-J Day. An

incredibly detailed day-by-day account of the residency is provided at

blackmarketclash.com (click on the link for 1981, then click on each Bond's

date). Also check out the Westway to the World DVD, which includes Don

Letts' documentary footage of Bond's. And dig these articles by Ira Robbins

and Jonathan Lethem.

I've found references to only a few other rock shows, including Wendy O.

Williams (yes, a car was blown up), the Blues Project (I don't recall Al

Kooper mentioning this one in Backstage Passes and Backstabbing

Bastards), Blue Oyster Cult, and a one-off night featuring members of

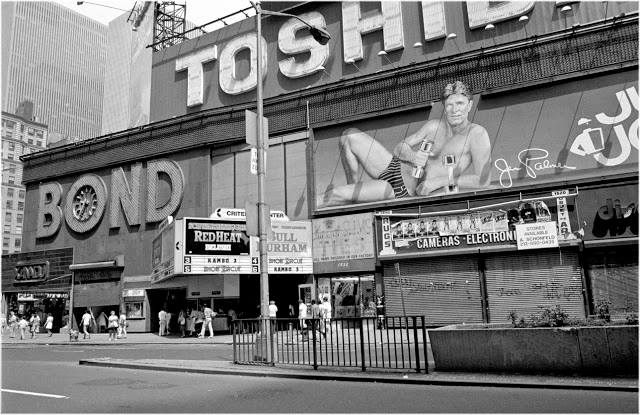

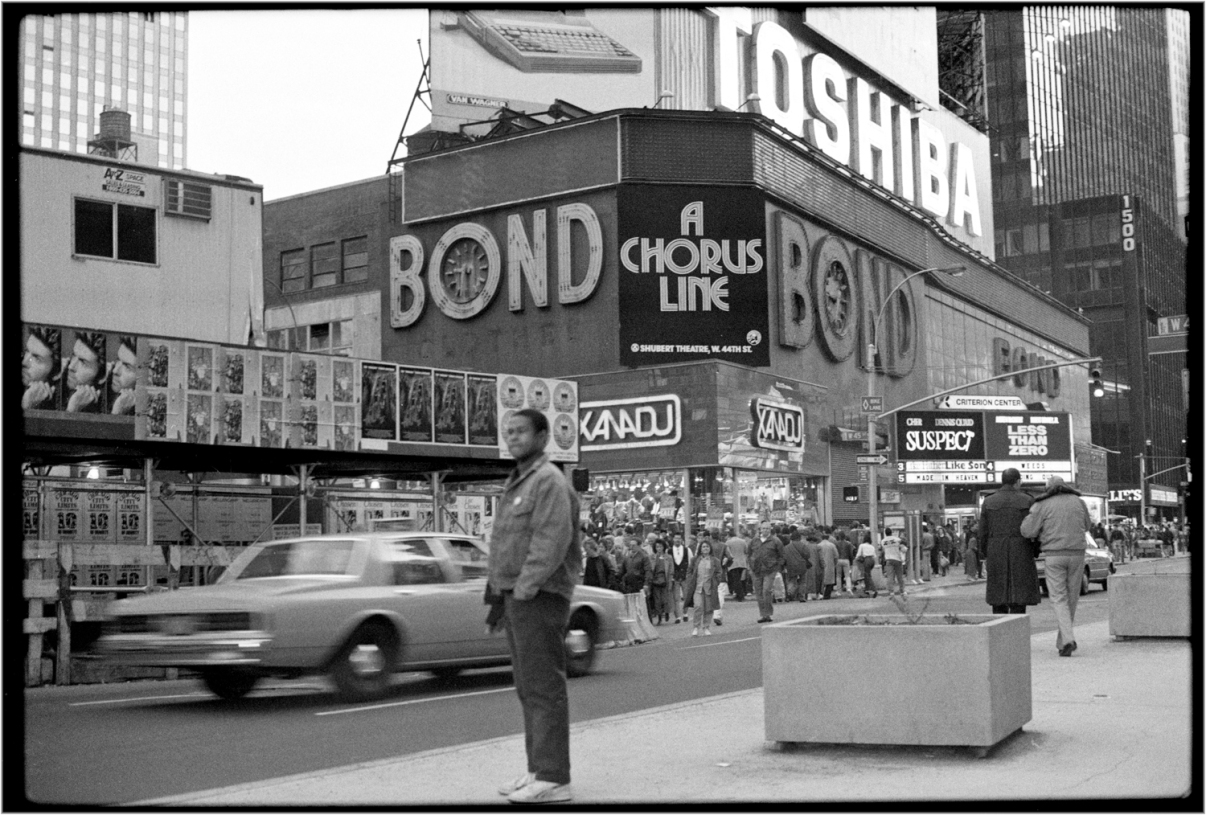

Blondie and Chic. It's unclear just when Bond's closed, or what, if anything,

occupied its space from the mid-'80s to the mid-'90s--but the neon BOND

sign remained in place for quite some time.

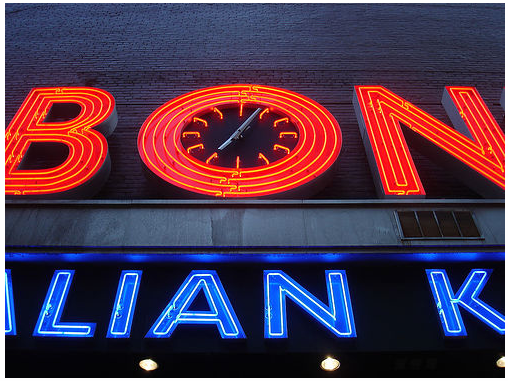

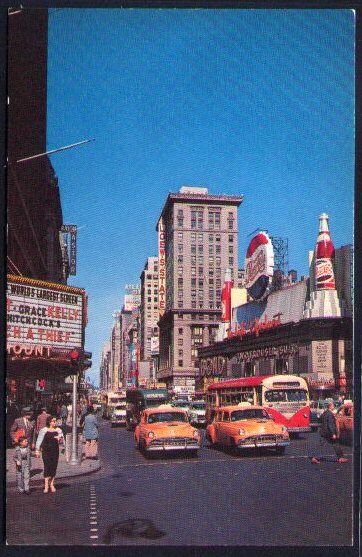

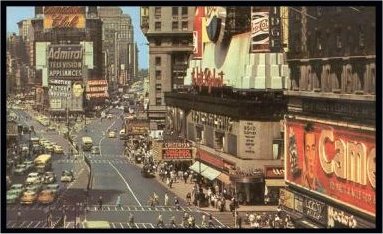

The Criterion Building still exists, but it looks nothing like it did in the old postcards. Now called the Bow-Tie Building (a reference to the shape of the Times Square intersection when viewed from above), it's owned by members of the same Moss family who have had interests in the structure since its 1936 inception. The Roundabout Theater Company rented space in the building through much of the '90s, but I'm not sure which part they used. The Criterion Theater, which spent its last few years as a muchmaligned multiplex, closed in 2000. Most of the building is now occupied by the flagship Toys R Us, a Foot Locker, and a Swatch emporium. There's no BOND sign facing Broadway anymore, but if you go around the corner on 45th, you'll find a smaller facsimile on the side of the building, attached to an old school-inspired Italian restaurant called Bond 45.

The Bow-Ties that Bond

http://streetsyoucrossed.blogspot.co.uk

BOND INTERNATIONAL CASINO--1530 Broadway, on the east side of Broadway between 44th and 45th Streets. (Often referred to as Bond's.) A short-lived discotheque most famous for hosting the "Clash on Broadway" residency in 1981, Bond's sat on one of the Times Square-iest spots of land in Times Square. This New York Times article summarizes its phases well, but I'll add some elaboration here, as is my wont.

Before the Times set up shop in the area, Longacre Square was the horse dung-scented center of New York's carriage trade. An unseemly spot indeed for the future Crossroads of the World, but as the city's entertainment districts had been inexorably migrating ever further uptown along Broadway throughout the 19th century, the Square's eventual colonization by the theater crowd was inevitable.

Oscar Hammerstein I was the earliest impresario to venture there. In 1895, on the site of the former 71st Regiment Armory (destroyed in a fire), he opened the Olympia Theatre, a massive Beaux Arts complex comprising a 2,800-seat Music Hall, a 1,850-seat playhouse called the Lyric Theatre, a smaller Concert Hall, and a roof garden theater.

According to Anthony Bianco's Ghosts of 42nd Street (New York: HarperCollins, 2004), admission was fifty cents, and patrons could wander between the theaters at will. "[T]he Olympia did not style itself as a family entertainment venue," writes Bianco. "Content to leave the middle of the road to others, Hammerstein experimented with provocative new acts and formats that expanded vaudeville's boundaries."

Hammerstein's adventurous fare included operas (some of which were his own compositions), "Living Pictures" (tableaus presented partially in the nude), Isham's Octaroons (an African-American song-and-dance troupe), and a notoriously so-bad-they're-good act called the Cherry Sisters. Unfortunately, not every production he put on was a financial success, which led to a foreclosure on the property after only three years of operation.

The building was auctioned off, and the theaters became separate entities under the auspices of different producers. Hammerstein's next local enterprises, the smaller-in-scale Victoria and Republic Theatres, were more lucrative. Meanwhile, the Music Hall was renamed the New York Theater, and was converted into a movie/vaudeville house when Loew's took it over in 1915.

The Lyric was first renamed the Criterion, then became a movie house called the Vitagraph in 1914, only to revert to the Criterion moniker a couple of years later. In 1907, Flo Ziegfeld staged his first production of Follies at the rooftop garden theater, renamed Le Jardin de Paris.

When he decamped for the New Amsterdam in 1913, the roof garden was converted into a dancehall called Jardin des Danses. Despite its many virtues, the magnificent Olympia building did not outlast the Depression; it was demolished in 1935.

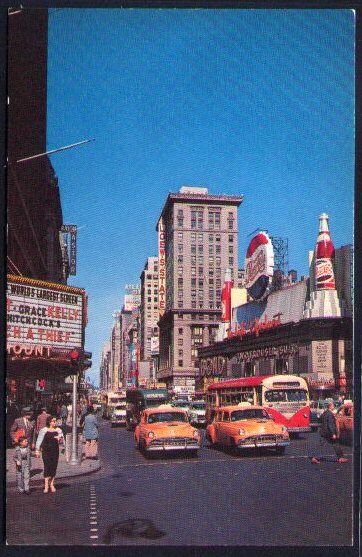

A year later, the Criterion Building rose in its stead. It occupied the same block-long frontage, but was not nearly as tall as its predecessor--unless you include the height of its huge rooftop neon sign, a fish-festooned spectacular advertising Wrigley's Spearmint Gum.

The building featured a new Criterion movie house (designed by Thomas Lamb and Eugene de Rosa), ground-level retail space, and a fabulous Art Deco nightclub/restaurant called the International Casino. According to Susan Waggoner's Nightclub Nights: Art, Legend, and Style, 1920-1960 (New York: Rizzoli, 2001), this Casino had nothing to do with gambling:

Once one passed through the solid brass doors and into the red and gold mosaic lobby, there was no shortage of amusements. The Cosmopolitan Salon was fitted with a small stage and littered with settees that could accommodate nearly eight hundred. Another one hundred and sixty could quench their thirst at the Spiral Bar, a curved slide of polished mahogany that swept from the ground floor up to the mezzanine. All this was a mere warm-up for the main room, where tiered platforms assured all fifteen hundred diners an unobstructed view of the show.

The show, mounted on an elaborately high-tech motorized stage, featured such delights as "novelties from five continents and the beauties of ten countries," an orchestra "whose reed section might suddenly plunge from sight, like riders on a parachute drop," a fanciful "Ice Frolics" revue, comedians like Milton Berle, and gorgeous chorines with gams for days.

The swank Streamline Moderne surroundings were "designed by Donald Deckie, who later designed the Radio City Music Hall," according to Anthony Haden-Guest's The Last Party (New York: William Morrow, 1997). However, the Casino may have been too gloriously grandiose for its own good; much like the Olympia, it closed after a mere three years in business.

Bond Clothes took over the Casino's space in 1940, moving from its previous location adjacent to the Palace Theater a couple of blocks north. In its new digs Bond styled itself as the world's largest men's haberdashery, and offered some women's wear as well. As if the store's famous "TWO TROUSER SUITS" neon sign weren't enough, beginning in 1948 it also boasted the most splendid spectacular ever to grace the Great White Way, designed by Douglas Leigh for Artkraft-Strauss. As described in Leigh's 1999 Times obituary:

At the base of the Bond sign was an electric news zipper, about five feet high, running along the entire facade. In Mr. Leigh's design, twin 50-foot-high figures, one male and one female, flanked a waterfall 27 feet high and 120 feet long. Strands of electric lights seemed to clothe the chunky classical figures at night, but by day they appeared naked.

Those loincloth-lights were added only after guests at the Hotel Astor across the street complained about the statues' scandalously starkers state. A clock poised above the waterfall perpetually reminded the public, "EVERY HOUR 3,490 PEOPLE BUY AT BOND." (I suppose an even 3,500 customers per hour would have been too much to handle...)

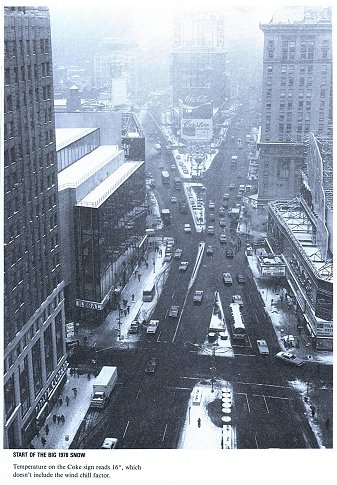

After six good-looking years, the sign was replaced with a Pepsi ad; the waterfall remained (and kept gushing until the early '60s), but was now flanked with giant Pepsi bottles. Apparently a Chevy ad was once meant to take Pepsi's place, but a garagantuan Gordon's Gin bottle and a smoking Winston man (a total Camel sign rip-off) eventually appeared there instead. The ground-level storefronts evolved over time as well--among the successive occupants were Woolworth's, Whelan Drugs, King of Slim's Ties, Loft's Candy, Regal Shoes, Disc-O-Mat Records, tourist tchotchke outlets, and those ubiquitous bad-deal '70s/'80s electronics stores.

Bond Clothes sold its last two-trouser suit in 1977, and after a couple of vacant years, the space was respectfully rechristened as Bond International Casino, supposedly the largest disco the world had yet seen. As described in The Last Party, the club was co-owned by John Addison and Maurice Brahms. It opened in July 1980, and featured such accoutrements as a "musical staircase," fountains retrieved from the set of The Liberace Show (which often ended up filled with near-naked patrons), and a wide-ranging music policy (usually spun by resident DJ Kenny Carpenter). However, according to these opinionated folks on discomusic.com, the joint never quite caught on, for various reasons--bad location (Times Square at the height of its sleazy-seedy era), poor acoustics, lack of an atmospheric theme, inconsisent musical choices, and above all, too much space to fill on a nightly basis.

There were no such space-filling difficulties during the Clash's booking in May-June, 1981. The buzz surrounding their initial eight-night stand was so high that the shows were dangerously oversold--3,500 tickets for each night, at a venue with a legal capacity of about 1,800. The FDNY threatened to shut the place down following the first two overcrowded nights. After much negotiation with city authorities, the band worked out a deal wherein they would play as many shows as it would take to honor all ticket holders--an unprecedented seventeen concerts. Times Square hadn't seen that much commotion since Frankie at the Paramount, or V-J Day. An incredibly and obsessively detailed day-by-day account of the residency is provided at blackmarketclash.com (click on the link for 1981, then click on each Bond's date). Also check out the Westway to the World DVD, which includes Don Letts' documentary footage of Bond's. And dig these articles by Ira Robbins and Jonathan Lethem.

I've found references to only a few other rock shows, including Wendy O. Williams (yes, a car was blown up), the Blues Project (I don't recall Al Kooper mentioning this one in Backstage Passes and Backstabbing Bastards), Blue Oyster Cult, and a one-off night featuring members of Blondie and Chic. It's unclear just when Bond's closed, or what, if anything, occupied its space from the mid-'80s to the mid-'90s--but the neon BOND sign remained in place for quite some time.

The Criterion Building still exists, but it looks nothing like it did in the old postcards. Now called the Bow-Tie Building (a reference to the shape of the Times Square intersection when viewed from above), it's owned by members of the same Moss family who have had interests in the structure since its 1936 inception. The Roundabout Theater Company rented space in the building through much of the '90s, but I'm not sure which part they used. The Criterion Theater, which spent its last few years as a much-maligned multiplex, closed in 2000. Most of the building is now occupied by the flagship Toys R Us, a Foot Locker, and a Swatch emporium. There's no BOND sign facing Broadway anymore, but if you go around the corner on 45th, you'll find a smaller facsimile on the side of the building, attached to an old school-inspired Italian restaurant called Bond 45.

Posted by Signed D.C. at 12:22 PM

Labels: Bond Clothes, Bond International Casino, Bow-Tie Building, Clash, Criterion Theater, Olympia Theatre, Oscar Hammerstein, Times Square

1 comment:

Mike Fornatale said...

<< the Blues Project (I don't recall Al Kooper mentioning this one in Backstage Passes and Backstabbing Bastards) >>

This was their second "reunion" show, the first having been in Central Park in the mid-70s. This show was broadcast live on WNEW-FM, and a couple of bootleg LPs exist. Veryb nice version of "Jelly Jelly," sung by Danny Kalb, which Kooper introduces this way: "For those of you listening to this at home on the radio -- it may be 1981 where you are but it's 1966 in here. Tell 'em about it Danny!"

9:12 PM

Post a Comment