Rolling Stone Magazine

The Clash: There’ll Be Dancing in the Streets

Tough but tender, they're taking America

BY JAMES HENKE - APRIL 17, 1980

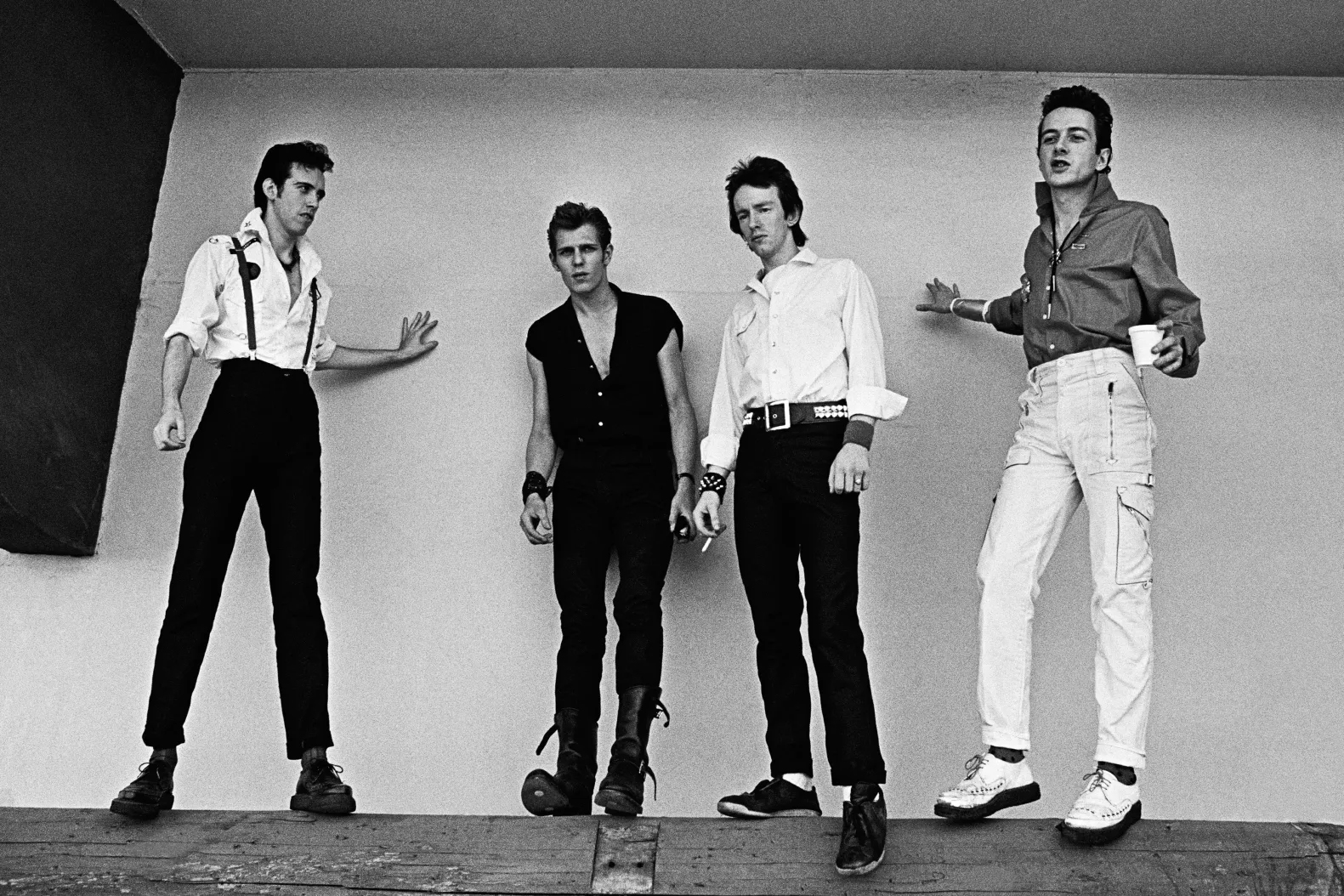

The British punk rock band The Clash (L-R) Mick Jone, Topper Headon, Paul Simonon, Joe Strummer during a stop on the group's 'Pearl Harbor '79' tour in Monterey, California. GEORGE ROSE/GETTY

WHEN PEOPLE SAY that we’re a political band, what they usually mean, I gather, is that we’re political in the way of, like, left and right—politics with a capital ‘P,’ right? But really, it’s politics with a small ‘P,’ like personal politics. When somebody says, ‘You can’t do that,’ we think you should stand up and ask why, and not go, ‘Well, all right.’

—Paul Simonon bass player, the Clash

“You don’t understand, mate. You just can’t leave those chairs there.” Joe Strummer, the Clash’s lead singer and rhythm guitarist, is really wound up. He takes another puff off his cigarette and moves closer to the manager of San Francisco’s Warfield Theater. “Don’t you see,” Strummer continues in an urgent, guttural whisper, “people will fuckin’ destroy those chairs, rip ’em right out. They come here to dance, and that’s what they’re gonna do. I don’t wanna see kids smashed up against the stage in front of me just because there’s not enough room to dance.”

The Warfield 1 March

In a few hours, the Clash are supposed to be onstage at this 2200-seat art-deco palace in the first date of a nine-shows-in-ten-days blitz of the U.S. The tour comes on the heels of the group’s grueling, two-month trek through the U.K., and just before bassist Paul Simonon is due in Vancouver, where he will begin working with ex-Sex Pistols Steve Jones and Paul Cook on a film in part about an all-girl rock & roll band.

Photos: Punk Pioneers Iggy Pop, Darby Crash and Other Icons

But despite this hectic schedule, the Clash and their U.S. record company, Epic, realized they had to strike now. After watching their first two critically acclaimed albums go virtually ignored by radio stations and record buyers in this country, the Clash released London Calling earlier this year. Broader and more accessible than its predecessors, the album — a two-record set that sells for little more than a single record — was immediately picked up by FM radio. After only six weeks, it is in the twenties on the charts and has sold nearly 200,000 copies. At this moment, though, the Clash are faced with another problem: they feel that some of the halls selected for this tour aren’t right for them — they have chairs secured to the floor, leaving little or no room for dancing.

“Just take out a coupla rows,” Strummer pleads.

“But we can’t do it,” the manager replies. “It’s too late. Besides, kids have tickets for those seats. Your fans waited in line for hours to get those seats.”

“Good,” says Strummer. “If they’re our fans, they won’t mind, ’cause they’ll wanna be standin’ anyway.”

“So what do we say when they come in with tickets and their seats are missing?”

“You tell ’em Joe Strummer took ’em out so they could dance. If they’re upset, we’ll give ’em a free T-shirt or somethin’.”

“But it’ll take hours.”

“We got lots of people here who can help. I’ll get down on my hands and knees and help if I have to.”

“We just can’t do it….”

A little more than an hour later, the front two rows of seats have been removed. And Joe Strummer didn’t even have to get down on his hands and knees.

With the possible exception of the Sex Pistols, the Clash have attracted more attention and generated more excitement and paeans from the press than any other new band in the past five years. Their first LP, The Clash, released in England at the height of the punk movement in 1977, has been hailed by some critics as the greatest rock & roll album ever made. Its fourteen songs jump from the record with such ferocious intensity that they demand that the listener sit up and take notice — immediately. But perhaps even more important are the lyrics. While the Sex Pistols and other punk bands viewed the deteriorating English society with a sort of self-righteous nihilism, the Clash observed it through a militant political framework that offered some hope. Certainly a long battle was ahead, they suggested, but perhaps it could be won.

Considered too crude by Epic Records, The Clash was never released in its original form in the U.S. Instead, a compilation LP that included ten of the album’s cuts plus seven songs from later British singles and EPs was issued in 1979. (Nonetheless, the English version of The Clash is one of the biggest-selling imports ever.) Those British 45s expanded the group’s musical range and lyrical attack, and made it clear that this was a group of musicians determined to leave its mark on rock & roll.

With its immense guitar sound, their second album, Give ‘Em Enough Rope, recorded with Blue Öyster Cult coproducer Sandy Pearlman, pushed things even further. The LP prompted critic Greil Marcus to write, “The Clash are now so good they will be changing the face of rock & roll simply by addressing themselves to the form — and so full of the vision implied by their name, they will be dramatizing certain possibilities of risk and passion merely by taking a stage.”

With London Calling, the Clash have matured on all fronts: the playing is more skilled and relaxed, though no less intense. The songs draw on a wider variety of influences — rockabilly, R&B, honky-tonk, reggae — and cover a broader range of topics, from Montgomery Clift to the Spanish Civil War to the Tao of Love. And the group’s sense of humor, which had been buried before by their Sturm und Drang, is more evident than ever. Some of the credit must go to producer Guy Stevens, a legendary British music-business eccentric. Stevens, who among other things produced four LPs for Mott the Hoople, a band that influenced the Clash, found a way to capture all sides of the Clash on record.

“‘Clash City Rockers’!” Shouts Joe Strummer, slamming his mike stand to the floor of the Warfield Theater stage. Immediately, Mick Jones rips into that song’s power-chorded intro, and the American leg of the Clash’s “Sixteen Tons Tour” is officially under way.

“We’re gonna do a song about something that no one here can afford,” Strummer says the instant “Clash City Rockers” ends, and the band bashes out “Brand New Cadillac,” a rockabilly oldie covered on London Calling. From there they tear into “Safe European Home” from the second album; next, keyboardist Micky Gallagher, on loan from Ian Dury’s Blockheads, joins them onstage, and the group launches into “Jimmy Jazz.”

Like the Who, the Rolling Stones in their prime or any other truly great rock & roll band, the Clash are at their best onstage. The music, delivered at ear-shattering volume, takes on awesome proportions; for nearly two hours, the energy never lets up. Strummer, planted at center stage, embodies this intensity. Short and wiry, his hair greased back like a Fifties rock & roll star, he bears a striking resemblance to Bruce Springsteen. When he grabs the mike, the veins in his neck and forehead bulge, his arm muscles tense, and his eyes close tight. He spits out lyrics with the defiance of a man trying to convince the authorities of his innocence as he’s being led off to the electric chair. His thrashing rhythm-guitar playing, described by one friend as resembling a Veg-o-matic, is no less energetic.

But the Clash also convey a sense of fun, the spirit of a celebration. As Mick Jones and Paul Simonon race back and forth across the stage, and as Topper Headon flails away at his drums, you can’t help but want to dance. And that’s exactly what this audience — a surprisingly mixed crowd of punks, longhairs, gays and straights — is doing. Everyone is on their feet. Hundreds are mashed together, dancing, at the foot of the stage, while at the rear of the hall, people are bobbing up and down in their seats.

After eighteen songs, the Clash leave the stage. The band returns with Mikey Dread, the dub singer who opened the show (dub is a form of reggae popularized by Jamaican DJs who talk, chant and sing over backing tracks). The first song of their encore is “Armagideon Time,” the B side of the English “London Calling” single. As a white spotlight pierces the ominous blue stage lights and focuses on Strummer, he begins intoning the lyrics: “A lot of people won’t get no supper tonight/A lot of people won’t get no justice tonight/The battle/Is gettin’ harder …” Coupled with Jones’ scratchy guitar lines, Simonon’s mesmerizing bass and Gallagher’s loping organ fills, the effect is eerie. When Mikey Dread begins chanting “Clash, Clash” near the end, the whole scene takes on an air of frightful prophecy. Five songs later, the show is over and the fans begin to leave. Outside on Market Street, one can’t help but notice the movie marquee abutting the Warfield’s. It reads “Apocalypse Now”.

“There, I gotcha!” Joe Strummer snaps the shutter on his brand new Polaroid SX-70 Sonar camera, and out shoots another photo — in this case, one that will bear my likeness. Fresh from an early-afternoon shower, Strummer has agreed to sit down and talk with me before he has to leave for a sound check. But right now the most important matter at hand is his new camera.

“Some girl had one of these backstage last night, and I couldn’t believe it,” he says. “She said it only cost $100, so I went out looking for one after the show. The first place I went, they cost $500 or something — way out of my current reach. But then we went to Thriftimart, and it was only eighty-eight dollars. Incredible!”

In some ways, Strummer is the least-accessible member of the Clash. “We’re totally suspicious of anyone who comes into contact with us. Totally,” he once told another writer from this magazine, and in his case it seems to be especially true. He tends to keep his distance when among outsiders, and often appears to stay on the sidelines when the rest of the band is involved in some sort of merrymaking. Twenty-seven years old, Strummer (born John Mellor) is the son of a British diplomat; his only brother, a member of Britain’s fascistic National Front, committed suicide.

“I GREW UP in a boarding school in Epsom, fifteen miles south of London,” he says, fidgeting with his camera, when asked about his childhood. “It’s not a lot to go back to, if you know what I mean. My dad was working abroad, and my mother was tagging along. I don’t think I really gave them a thought after a while.”

Strummer is extremely soft-spoken, and because many of his teeth are rotting or knocked out altogether, it’s often difficult to decipher exactly what he’s saying. “I found that I was just hopeless at school,” he continues. “It was just a total bore. First I passed in art and English, and then just art. Then I passed out. That was when I was seventeen; I left to go to art school. Boy, that was the biggest rip-off I’ve ever seen. It was a load of horny guys, smoking Senior Service, wearing turtleneck sweaters, trying to get off with all these doctors’ daughters and dentists’ daughters who got on miniskirts and stuff. And after I took a few drugs, things like that began to look pretty funny.

“Like, one day someone gave me some LSD, and I went back into the school, and they were doing this drawing. I was really shattered from this LSD pill, and I suddenly realized what a big joke it was. The professor was standing there telling them to make these little puffy marks, and they were all goin’, ‘Yeah,’ making the same little marks. And I just realized what a load of bollocks it was. It wasn’t actually a drawing, but it looked like a drawing. And suddenly I could see the difference between those two things. After that, I began to drop right off.”

Our conversation is interrupted momentarily when Strummer spots Mighty Mouse on TV. Apparently, he had failed in his attempts to photograph something off the television screen the night before, and the appearance of Mighty Mouse presents him with another opportunity to outwit the TV. After trying various techniques, such as covering the Sonar device with his hand, he finally succeeds, and we resume talking.

“Then I just spent a couple of years hangin’ around in London, finding no way to manage. I was studying this Blind Willie McTell number all day, and then I’d go down to the subway at night and strum up a few pennies [hence the name “Strummer”].

“That was when we moved into squatters’ land. They’re demolishing all this housing in London, and all these places are abandoned. People started kickin’ in the doors and movin’ in, so we just followed suit. You had to rewire the whole house, ’cause everything’s been ripped out. Pipes, everything. We’d get a specialist who’d go down to this big box underneath the stairs and stand on a rubber mat and take these big copper things and make a direct connection to the Battersea Power Station. Bang! Bang! I seen some explosions down in these dark, dingy basements that would just light things up.

“There’s a state of poverty where it gets to be good fun. I was fuckin’ useless at all this, but some of the guys I was hanging out with, they could do anything. And that’s where I started to rock & roll — in the basement of one of those places. I remember we had an acoustic guitar and a pair of broken bongos, and we built up from there.”

Eventually, a band called the 101’ers (named after the street address of the “squat”) began making a name for itself playing R&B in pubs around London. The group recorded a single, “Keys to Your Heart” on Chiswick Records, before Strummer left to join the Clash. “As long as I’d been pubbin’, I’d been really frustrated,” he recalls. “I was just lookin’ to meet my match, just lookin’ to stir things up. And when I was offered this job, I recognized that it was the chance I’d kinda been waiting for. Just the look of Mick and Paul, you know? The gear they had on….”

“I first saw Joe in the dole line,” Mick Jones tells me. “That’s no lie. We looked each other over, but we didn’t talk. Then we saw each other in the street a couple of times; eventually we started talking, and he wound up over at my flat.” That meeting took place in the summer of 1976. By then Jones had already formed the nucleus of the Clash with Paul Simonon and Keith Levine. (Currently a member of Johnny Rotten’s Public Image Ltd., Levine, a guitarist, left the Clash very early on.)

Unlike Strummer, with whom he writes the bulk of the Clash’s material, Jones is an extremely affable fellow. His dark, riveting eyes and his warm, goofy grin quickly put any newcomer at ease. He’s so short and skinny he looks as if he could be easily blown over. And like most of the other members of the band, he’s taken almost exclusively to wearing black-and-white clothes (“More subtle, don’t you think?”) and to greasing his dark brown hair back.

BOTH JONES AND Simonon are twenty-four, and both come from Brixton, a grotty working-class area in South London. “It’s pretty bleak, not paradise,” Jones says. “You know — lots of immigrants and that.” His parents split up when he was eight, and he was raised by a grandmother. Simonon’s parents also were divorced when he was young; he was raised by his father.

Prior to forming the Clash, Jones was attending Hammersmith Art School and playing in London SS, a musical forerunner of the British punk bands. Simonon, after a year of art school, was “sittin’ around, thinkin’ about what was gonna happen the next day, where I was gonna get my dinner, things like that.” He had never played bass before he joined the Clash.

“We just sort of bumped into each other,” Simonon says of his first meeting with Jones. Though he comes across as the toughest member of the group, the tall, lanky Simonon, with his dirty-blond hair and chiseled features, has the look of a matinee idol. “I was goin’ out with this girl, and she was friends with this drummer. Mick was lookin’ for a drummer, and he invited this bloke to rehearsal. I just turned up, and that was it.”

Under the guidance of then-manager Bernard Rhodes (a one-time associate of Sex Pistols chieftain Malcolm McLaren, and reportedly a key influence in the development of the Clash’s political stance), the Clash signed a reported $200,000 contract with CBS Records in February 1977. Their first album, recorded with drummer Terry Chimes (renamed Tory Crimes for the occasion), followed soon afterward.

“That one was a pretty special record,” Jones recalls. “We did it in three weekends — nine days. We were sprinting. That’s what that whole period was like — sprinting.”

Drummer Chimes left the group shortly after The Clash was recorded; eventually, Nicky “Topper” Headon was recruited as a replacement. Something of a journeyman drummer, Headon, 24, comes from a middle-class family in Dover and still retains a fairly normal, middle-class appearance. His father is headmaster of a primary school, and his mother teaches. He left home at sixteen and moved to London, where he played in bands that ranged from soul revues to traditional jazz outfits, even doing a stint with heavy-metal guitarist Pat Travers. “I left London to join one of those soul bands that was going to Hamburg,” he recalls. “I don’t think Mick will ever forgive me.”

But, in fact, it was Jones who recruited him for the Clash. “We ran into each other at a concert,” Jones says. “I asked him how things were going, and he said great. Then I mentioned that we were looking for a drummer, and he jumped at it. The only thing I told him was that he’d have to get a haircut.”

And I move any way I wanna go

I’ll never forget the feeling I got

When I heard that you’d got home

An’ I’ll never forget the smile on my face

‘Cos I knew where you would be

And if you’re in the Crown tonight

Have a drink on me

But go easy

step lightly

Stay free.*

“You made me cry out there, man.” Freddie, A nineteen-year-old Englishman transplanted to San Francisco, grabs Mick Jones around the shoulders and gives him a big hug. Jones gently pulls away, his dark eyes staring mournfully at Freddie. “I made you cry? How do you think we’re gonna feel when they bring you back with a hole in your chest?”

Backstage at the Warfield Theater on Sunday night, the Clash have just completed their exhilarating second and final show in San Francisco. Near the end of the set, Jones dedicated “Stay Free,” a song from Give ‘Em Enough Rope, to “someone I know who’s going into the marines tomorrow.” And now Freddie, that someone, has come to thank him.

“Aw, come on, man,” Freddie says. “Stop it. You’re making me cry again.”

“I mean it,” Jones says, his sadness almost turning into anger. “What the fuck do you think you’re doing? One way or another, you’ll never come back alive. They’ll ruin you.” Jones pauses and surveys Freddie’s rock-hard physique. “Freddie here used to be as skinny as me,” Jones says, turning to me. “We used to see him at our shows in London. Now look at him. He’s joining the marines,’boot camp,’ I think he called it.”

Freddie, straining to hold back tears, is obviously shaken. “But Mick, it’s a roof over my head and $500 a month,” he protests.

“FIVE HUNDRED DOLLARS a month!” Jones erupts. “Fuckin’ lot of good that’ll do you when you got a hole through you.” Jones stops and looks around the dressing room. He spots Kosmo Vinyl, the band’s assistant, PR person and jack-of-all-trades. The two huddle for a few seconds, then leave the dressing room.

Finally, Jones wanders back in. I ask about Freddie.

“He’s not goin’,” Jones says. “Me and Kosmo and Joe will give him the $500 a month. He’s coming to work with us.”

A little later that evening, I run into Jones in a corridor at a party being thrown for the band by Target Video, a company that makes New Wave video-cassettes. “Look, if you wanna talk, let’s talk now, he says, leaning against a wall. “I’ll have more to say now than I will later.” Soon we’re into a discussion of the draft.

“If I lived in America and the government was talking about war and about starting the draft again, I wouldn’t just be sitting there,” he says. “You’d think people in America would be more aware. I mean, Vietnam wasn’t that long ago. They should know not to believe for a minute that it’s good. I went to a church this morning’, and you know what those people said? They said if the country goes to war, we’ll go. Maybe we can help some guy in the trenches. Is that right?”

I ask what he’d do if England started the draft again.

“We’d start our own antidraft movement.”

Would he go to war?

“That’s out of the question. This is an important fact: people prefer to dance than to fight wars. In these days, when everybody’s fighting, mostly for stupid reasons, people forget that. If there’s anything we can do, it’s to get them dancing again.”

After a minute or so of silence, I ask about the new album. It was recorded during a rough period for the band. The group had just split with its second manager, Caroline Coon, and settled a lawsuit with her predecessor, Bernard Rhodes. In one interview, Strummer was quoted as saying they felt the LP was their last chance.

“We were more introspective,” Jones says. “We were fed up with things. We were also quite miserable. Miserable gray old place, London is. Very oppressive. Things are going very badly there.”

Why then, I ask, does the album seem more relaxed, more playful?

“Well, some of it is relaxed, but not all of it. I don’t call ‘London Calling,’ ‘The Guns of Brixton,’ ‘Clampdown,’ ‘Brand New Cadillac’ relaxed. I certainly don’t think it’s fair when people charge that we’ve mellowed out.”

But the music is more accessible.

“We realized that if we were a little more subtle, if we branched out a little, we might reach more people. We finally saw that we had just been reaching the same people over and over. And the music — just bang, bang, bang — was getting to be like a nagging wife. This way, if more kids hear the record, then maybe they’ll start humming the songs. And if they start humming the songs, maybe they’ll read the lyrics and get something from them.”

I ask what it is he’s trying to achieve, what his goal is.

“My goal is like a mountain, a very big mountain. And it’s gonna take a lot of gear to get up to the top. You know what it’s like? It’s like banging your head against the wall. There are some victories, but they’re small.”

Do they even out in the end?

“I’m not sure they do; I think we’re getting beat. It’d be nice to be a band that people didn’t have so many preconceptions about, one that’s not the hip thing to like. When we can go onstage and play what we want-jazz, maybe — and not have to do what people expect, that’ll be a big step forward.”

That said, we go back out into the main room, where some of the great Motown songs from the Sixties are blaring from the sound system. And where everyone’s dancing.