Paul Morley of the NME travels on the tour bus from Detroit on the 17th through to New York on the 21st interviewing and following the band

DETAILS: The Scene.

The Clash on tour of America. There's a glamorous image, with a confident, crusading edge to it.

The Clash: a lot of hope and responsibility there. America: it still means a lot.

Clash's current six week coast to coast tip to toe tour of the United States Of America is their first major assault upon the stupefied standards of the land. It follows a few months after their exploratory dip into the stagnant, dense culture waters of America — a six date trip definitively chronicled by Joe Strummer's own frantic pen in the NMEof March 3rd, 1979.

The tour— titled Take The Fifth' — possesses a resistance and direction that sets it well apart from the soft centred, soft hearted British invasion of Sniff 'N' The Tears, The Records, lan Gomm, Bram Tchaikovsky, et al. The Clash are in America following destiny. The tour has taken on the spirit of a quest. The Quest: abstract words with a definition much the same as 'punk'. Newchange and choice...

In America this is about working towards less Kansas, Styx, Foreigner and Boston and more reggae and Clash on the radio; towards replacing the glazed look in the eyes of American youth with a glint of purpose and passion, towards staying alive, towards saying 'look out'. The Quest is a battle requiring non stop concentration, humour, flexibility and understanding. Blind faith, even.

Joe Strummer will refer to the unknown American audience as the great grey people, maybe something ultimately unreachable. "You know how we can get through here," Strummer will reflect, "I want to get through to the person in high school; you know, all the people that we've got to in the cities, they're sussed, right, it's the kid in the high school who doesn't know anything about it even yet. I hope ultimately we get through to him. Because he's the one at home in his bedroom, he's got Kansas albums and racks of Kiss and all that, and I feel like he should have a dose of us."

But perhaps, paradoxically, it's a victory that The Clash must never complete: "To sell something like Rod Stewart here, that's going to mean that we reach all the nurds, they're gonna have to go out and buy a copy, right, and they ain't even gonna do that because they never heard of us . . . but maybe that's why we are never going to get there; because once you get there, you're fucked. You know what I mean? Maybe we'll never get there."

It's an end—commercial success—that The Clash shove in a corner. "If we were just going to be another Stones or another Who," Strummer told a Detroit newspaper, "it would be a bit of a bore. That's why we're going to try and turn left where we should've turned right, y'know."

The Clash try to live from day to day. The Clash are in America for better or worse; it's a shot-gun wedding of sorts. They are committed to convincing America that there is something wrong. There is no easy way.

I spent nine days with the group, the first' • part of their stint, about a fifth of the total. I glimpsed the pain and pressure, a little bit of the pleasure, shared a lot of the monotony and frustration. There was some jealousy, but ultimately a gladness that I wasn't in what they were in. Mixed up with love, admiration, confusion; that's this writer's cocktail.

The Clash have surrounded themselves on the tour with a lot of people. Girlfriends Gabrielle (Strummer), Dee (Headon), Debbie (Simonon); publicist, clown and one of the most important people in rock'n'roll, Godfather of the Quest Kozmo Vinyl; photographer Pennie Smith; cartoonist Ray Lowry; DJ Barry Myers; personal roadie Johnne Green. Already this circus of creativity has been reported as unnecessarily unwieldy —the way music papers transmit fragmented fractions of truths that negatively pad out the glamour image is one of the things that frustrated me about the tour. These fellow travellers were all invited on to the tour, were not a buffer, and did not cramp The Clash. If energies weresplit and diverted that's the only way it could be. At least the energy was there.

The Clash love to be with people, and shared their touring coach to bursting point with no complaints. They feed off others' energies. This is one reason so many on the road adventures of The Clash turn up in the pop press. My own presence, if unwelcome, would have been quickly discarded. The Clash are hardly tolerant or submissive.

Reports have indicated that such an unwieldy entourage suggests confusion. Of course The Clash are confused. In such unnatural circumstances who wouldn't be? This confusion is more positive than harmful. There is nothing slick or pre-planned about The Clash, who were literally living, financially, from day to day on the tour, not able to be certain that hotels two days ahead were booked. Reports that the group were smothered in money from Epic are silly and laughable; at one point the group was forced to seriously discuss coming home.

There is still confusion over Clash management. On the tour, at certain points, up to four people would be telling the individual members of the band what the next move was. This caused misunderstanding, a lot of waiting, a lot of muttering under the breath. It emphasised that The Clash are not a business; they are still an amateur organisation, and whilst this can be frustrating it's positive in that the essence of Clash is not set, sealed and unchanging. There is nothing certain about The Clash. Nothing comfortable. No chance to sit back.

Joe Strummer, Topper Headon, Paul Simonon and Mick Jones live The Clash. Touring America is a long hard job with no distinction between work and play, where things constantly shove into the mainline preoccupations of travelling, soundchecking, sleeping and performing. Distractions like round the clock newspaper / radio / tv interviews. Distractions like attempting to package, title, and even mix their third LP, knowing at the back of their minds that decisions often made snappily or jokingly will stick around them for a long time to come.

Distractions like fighting to insist that the record will be a double for the price of a single, knowing that if their demands get ignored by faraway CBS they will be the ones to face the cynical derision.

The third LP is going to contain 18 songs. Songs they took to writing as part of the recovery from the spiritual low they experienced at the beginning of the year. "Black music, black vinyl, black and white cover."

But there's nothing about The Clash that is straightforward. They concentrate on biringing these long, tall and wide new songs into the set, thinking about the forthcoming release, and meanwhile their American label Epic have finally released the first LP, with the addition of a few recent songs to contrive a 'greatest hits' package. The Clash find themselves unwittingly and unwillingly having to promote relics from the past—that was that and now its now — songs that have a part in their set but little relevance in their new way of thinking.

Not only that, but whilst The Clash are away, CBS will play. CBS thought it would be a good idea to release the USA package in Britain. Full price and all that. The Clash are forced to fight this nonsense.

"What a threat," snaps Strummer, "just to pay for this jaunt!"

"Typical of them to try and trick us when we are away," snarls Jones. "They always do that. They thought that they cou Id make it look like the British fans would want the record and then it would pay tor us to come over here. We're not going to do that! How would that look? To the kids at home, some kid in Bolton:

'Oh yeah, I'm paying for them to ponce about in America'... so we've successfully put the block on that.

"We just said we would come back home if they did that," expands Strummer. "We were willing to go home straight away. Fuck it, we'd go home, bollocks to the rest of it."

On it goes. A ball of confusion bouncing wayward but forward. Vague ideas about visiting Mexico and Cuba are brought into play, introducing more problems. The curiosity of The Clash will never be curbed. Their ills of desire will never be cured. The reputation thickens, for better or worse.

This yet-another-lengthy NME support of The Clash is subjective details of the extent of their commitment, a commitment that is often . nothing more than a commitment to merely continuing. It is a report on the new responses; The Clash truly never look back.

It is a glance at fourt otally different characters who came together, became the strongest survivors of the punk purge because of spite, the ability to expand, the odd accident, a lot of stubborness and fear. They have had to struggle constantly with compromises, their naivity, their impatience, the scorn of those who are convinced that they've failed in their 'task', the sycophantic glee of those who observe in the group's desperation and dilettantism and arrogance the saviours of something or other.

Details from little bits of a story. The Clash story, like all the very best stories, doesn't start once upon a time, but is about limitation and potential, a search, and will not have a happy ending. It's thick with plot, the characters are complex and wonderful, and it's impossible to ignore.

It started something like this:

DETAILS: THE HISTORY

"Twenty one was when I first got sensible, when I learnt to play the guitar. Before that I was just poncing about," Joe Strummer tells me.

m school I went straight into art college, gnu utter a year I just went off and did absolutely nothing. For at least two years I was just bumming around. Everyone's gotta bum around. I worked on a farm but stayed round London most of the time, and then when I was 21 I thought right I'll get really -' serious now and I'll learn to play the guitar.

"When I was sixteen like everyone I had a Spanish flamenco guitar and I learnt to play some blues toons on it, then I thought well I can't handle any more of that so I never bothered. When I was 20 I felt sick that I'd never bothered, I thought 'Shit, I could be better than Eric Clapton.so now I'm 21 I'm really gonna do it. If I don't do it next year.I'm going to be even more pissed off'.

"So I just started, and having to earn my living with it helped. I ended up bottling for this busker, and it was like, I found out later on, the apprenticeship of a blues musician. I got a real kick out of that. All the great blues players started out collecting the money for some master, to learn the licks. The guy I bottled for would play the violin and eventually whenever there was a guitar lying around from another busker! would borrow it and he would teach me how to accompany. Just simple country and western and Chuck Berry.

"One day he said he was going off to do the pitch at Oxford Circus and he left me at Green Park and said' 'Now you do this pitch.' I had a ukeiele. He just walked off and left me alone. It was rush hour and the train emptied at one end of the corridor. One second the corridor was like empty, the next minute it was packed with people streaming through. It was like now or never, playing to this full house. That was the first time I remember performing on my own.

"I got good money but I had to give it up. I was walking along a curved passage at Oxford Circus and I happened to glance up at the ceiling at these speakers and I couldn't work out what they were, and I started playing and a voice said, from the box, speaking to me all on my own in this corridor, one flight under the city, this box was saying 'Right you clear off we're sending the railway police'. I realised these speakers were linked to the cop shop upstairs, where I was used to being dragged, but usually you had a chance to run off. But this was like—what can you do? This is 1984. This guy walked past and I screamed at him 'Can you hear that? This is 1984!'and he gave me a funny look and rushed off. I thought 'Aah fuck it' and packed it in.

"Then I was hanging around the Elgin Avenue, the Elephant And Castle pub there, and I was watching this Irish trio hacking out this stuff and I thought, 'Hey this is how to get over the summer', y'know, when my form of income was like curtailed because of the speaker system, I thought this is how to do it. , All these people were hanging round my squat just doing nothing and I thought I'll whip up a few of these guys and we'll play in some Irish pubs. I can do that. And that's how the ' 101'ers started, just to get over the summer I never thought we'd end up playing in the Windsor Castle, which seemed to me to be the be all and end all, never mind Madison Square Garden, that's what it seemed like to me.

"After busking for a while doing Chuck

Berry and blues tunes you start to switch around the chords when no one's looking. You start making up things in those endless hours • when no one's around. That's how I guess I started. I didn't really want to write songs cos I figured that I couldn't... I'd never been musical, I didn't know what I was getting into. I'd always been into the music ever since 'Not Fade Away', I'd always been a total number one fan, but I never thought that I could do it, expecially as I'd always been more into painting. I just ended up writing after trying everything else, by default.

"The 101'ers 'gigs were really chaotic, like h i ri ng a room a bove a pub, tenpence to get i n —- independent promotion I just realised that v^as. This girl said rent the room for a quid — A'QUID — and we can put on a club, and we can print circulars, and we were lying around going 'Leave it out, we'll never do that, no one'll ever turn up'. She pushed us into it and we had a thriving club going before we knew where we were. Every Wednesday night, packed with lunatics.

"It just seemed by default again, doing 'Boney Maroney' to a load of lunatics, and we only had six numbers so to fill it out I figured I was going to have to write something. I think the first thing I wrote was 'Keys To Your Heart'.

"It took a long time for me to meet up with Mick. I mean, from that time to the time I met Mick is almost the longest period of my life. It was six gigs a week for maybe eighteen months. Getting work was all by default as well. We got on te the pub circuit and we started getting one line mentions in the papers. After that started it was just a slog. It just seemed after doing eighteen months of that we were just invisible. I started to lose my mind, I would go around the squat saying, 'We're invisible, we should change our name to The Invisibles'. Cos I felt like we'd been doing great shows for three hundred people in Norwich or Thetford and it would just be invisible. You'd get back to London about 5 in the morning, unload the gear in the back room, put on a kettle and go'What the tuck's - all that about?'And in the paper it'd be likeQueen and all that. We were just shambling from one gig to the next banging our heads against the wall.

"As soon as Johnny Rotten hit the stand, right, the writing was on the wall. As far as I was concerned. I was in that state of mind that I was just slogging around getting nowhere. I sacked yet another guitarist because although he was a brilliant technician he didn't understand what I wanted. I got Martin Stone . into play some shows and that was fun but it just seemed that whole thing was over.

"Bernie Rhodes turned up at the Golden Lion with Keith Levine and I went outside and stood at the bustop with them and he sort of' ' said, "What you gonna do?' And I said, 'I . dunno,' and he said, 'Well come down to this squat in Sheperds Bush and meet these guys,' and Keith was sat there nodding saying, 'You'd better'.

"I met Mick the next day. I didn't even have no choice. The 101'ers were strictly a well known west London R&B band.

"When I met Mick and Keith at the squat we went in and sat on the bed and looked at each other and like Bernie said. This is the guy you gotta write songs with,' and Mick sort of scowled and I thought, 'Well I haven't got any choice. This is what I've got to do'.

"Finally we got playing and we'd play anything until we could think of something to write. Me and Mick were just sitting upstairs and I had a big notebook and I would just write the words out with a big crayon and he would bang out a simple tune. I don't know how it happened. I got no memory, really, no recall at ail. lean remember writing 'White Riot' and '1977' but the rest I can't remember.

"The whole thing was really great from the beginning of 1976 when my group crumbled and I met this lot and we took off, all the way through that. My dreams were like carnivals, • my mind would churn over and over in my sleep and I'd wake up and I'd been speeding naturally cos of the decisions, throwing in one thing and doing another, everything was being tried and experimented, i; was just great.

"It can't seem to be like that all the time but it's great when it is.

"We knew it was going to be good. You know that certainty when you don't even i; bother to think, that certainty was with us and ! I'ITI glad of it. We knew that this was it. I don't knbw how or why. "I loved the exposure that I got. Finally. I '^ . .

thought 'We'll show those bastards'. They'd been ignoring us, and when we got big reviews I just thought it was really something. It seemed like we deserved it.

"To be honest I'm a total idiot in the business affairs, more so then, I'm really dumb and naive now, and I'd freely admit that I didn't know what the fuck was going on, I hadn't got a fucking clue. Maybe it was because we were being so totally creative, like business decisions seemed totally irrelevant. It's like jazz musicians saying'Let me play the horn, don't bother me with details'. I was only happy that we were going to be able to put our stuff on record. When Bernie said we were going to sign to Polydor I just left it all to him and I just thought 'Fucking great, we can put out a record'.

"Signing for CBS was a good idea for us at the time because it was really a danger of if being us and The Pistols, we signed to major labels. The Damned went to Stiff, and then like we went in the Rainbow as well as that and the Pistols went off on the Anarchy tour with us bottom of the bill and like that was a conscious attempt on the part of McLaren and Rhodes to burst out of the confined thing. They'd been to New York and what they hated was that the punk thing was like CBGB's on the Bowery was how it stayed for five years. It never came out of there.

"And McLaren and Rhodes were right; our stuff and the Pistols' stuff was great. I don't want to blag, but it was great, and it didn't deserve to stay in a hole in Covent Garden for five years. Can you imagine us playing The Roxy Covent Garden for four years? I'm glad that McLaren and Rhodes had the suss to suss that, and that was like part of breaking out. We burst out when it needed to be taken seriously, y'know what I mean.

"Now people go 'Of course it was taken seriously', but in those days it was a novelty:

'Ha ha ha look at those idiots, pass me the Little Feat album'. And at least we fucking burst out. We had to."

DETAILS: THE TV SHOW

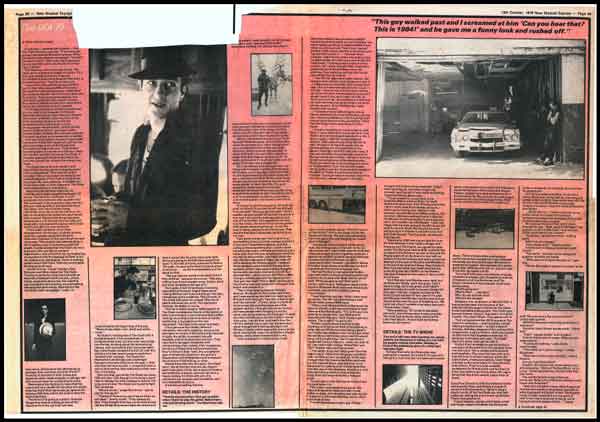

Two and a half years after bursting out, gaunt, twitchy Joe Strummer is sitting in a row with his equally restless comrades, blinking in front of the unblinking glare of a white heat television tight.

Perhaps that early Joe Strummer was looking for a reward. So is this it? It's part of it. Sitting in a room the size of a bathroom tucked away in the corner ot the New York Palladium squashed between Mick Jones and Topper Headon, preparing to play spokesman for a movement to the film camera of a well know American documentary programme, 20/20 which wants to know what this noise is all

about. Thirty minutes after concluding a performance that cracked his voice, blistered his hands and blurred his eyes, Strummer is expected to explain. And perhaps he'd better get it right. Millions will look on. Joe can't see it like that. He needs a drink.

Two and a half years, two albums of songs, a handful of singles, lots of questions and lots of answers, and Joe Strummer and The Clash's reward is to have people continually poking away.

What's going on?

What's this?. . .and that?

Why do you look like that?

Where's the change?

Whatever it is, revolution or idle chit chat, it has to be televised. And because of the defaults and the anger it had to be The Clash. It was inevitable looking back. The Clash have become known. Unique. Important. And still a novelty. They don't flinch. They get on with it.

That a programme like 20/20 comes to The Clash for comment — and hopefully a small helping of controversy — is both a sign of success, and also, because of the nature of the programme, a sign of failure. Clash areviewe as little more than hopeless eccentrics. To burst out in America isn't easy. The Clash don't shy away; they get on with it.

Kozmo Vinyl manages to get the group in one place at the same time and squeeze them into the room. The tv people smile genially and hopefully. The room has been set up so that the final on screen viewing will be the typical stark, crude punk setting. Clash fidget and sigh as the technicians fix microphones and camera. They're to play sensible spokesmen for British punk rock but they're tired, they want to go home. Duty, the vague sense that this is the reward, keeps them in place.

Suiet Paul Simonon, with the awkward frame ind beautiful face, contributes a couple of works to the conversation, fights to keep a slayful smirk off his hard features, and then walks out, letting the smirk break up his face. rhat'll look good on tv.

Topper Headon, sneaky and cheeky, small and tough, absent mindedly lets Strummer, draw a moustache on his slight face and then he departs too. Grinning condemning Mick Jones and a ltetchy Strummer do the talking, warming just a little to their subject. How cou Id they not? Off camera, the careful female voice prods,nudges and doesn't help the discontented duo into action..

.. 20/20 take six... I have to ask you some pretty dumb and stupid and obvious questions because a lot of people don't know anything about you or punk. '

Micky plays the good boy, teeth brea*<_ I through his lips. "Well, we are The Clash," he explains as if to a little child,"and we are a British punk band from London."

"Australia," grunts Strummer, looking away.

What is punk anyway?

"It's a music innit?" charms Jones.

Is there such a thing as American punk music?

"Not really," decides Jones, taking the question at safety pin literal.

"What about the Dead Kennedy's?" asks Joe.

"Mmm. But really it started in London in the mid '70s and we are the only survivors!" Jones eyes sparkle, i

What do the people who play punk have in common?

Simonon says his two words worth. "Short i hair."

"Yeah," agrees Jones" and no flairs."

Everyone says you're angry. What are you angry about?

"Fucking everything," spits Jones convincingly.

"The hotels ain't good enough," croaks Strummer. /

"Well we're quite happy actually," claims Headon.

Are you a political band?

Headon, Strummer and Jones break into a silly sing song. "We're A Political Band. La La La La." Jones decided they should write that, one down.

The careful female voice continues, unmoved: What's the difference between your music and American?

"Well this is English music. What happened to American music is completely opposite to what happened to English music. The English music is really exciting it's in the spirit of rock'n'roll; that's what we're doing, we're trying to remind people of that ..."Jones pauses. Strummer screams and clears his throat: "IT AIN'T ABOUT PLAYING THE RIGHT FUCKING CHORD FOR A START!" What is it about?

"I can't quite put my finger on it," Strummer sneers.

How do you feel about people buying your album? The commercial success?

Strummer: "Well, there's about three, people who've bought our album so far."

Jones; "I'd rather they bought burs than somebody else's."

Strummer: "We've sold three records and after this tour we'll sell another three." " What are you trying to do? You're on a tour of American and lots of people are seeing you, far more than three.

Strum'mer: "If we come to an American city there are approximately 2,400 people who come to see us, who know about us. On the other hand there are ten million zillion people who've never even heard of us in the city, especially those people who go to high school or low school or any other kind of school. I've been in their bedrooms in Virginia or Texas and I've seen their albums stacked up by the bed, and there's Kansas, Boston, Foreigner and I try to say to them. These records ain't no good, doncha know about the Yardbirds?' And they say 'Who?' And I say 'Doncha know about The Clash?' And they say 'Who?' And that's it. How are we going to get through to these people? They ain't rushing over to the radio station saying 'Put on a Clash record PUT ON A CLASH RECORD!' They ain't doing that."

Jones: "A lot of the radio stations in America aren't even playing black music ..."

Strummer: "Which is even worse! Never mind The Clash, what about where the music came from!"

Jones: "You're sitting in Minneapolis and you don't even know what reggae music is!"

Strummer: "For every satin-suited . ' platform-soled macho-strutting guitarist, for everyone of those up there in the lights sniffing coke, right, there's like 50 or 60 blackmen starving in the same town who invented the music with their own sweat, and this guy is ripping it off and posing away. It's shit!"

Jones and Strummer had by now successfully succeeded in pulling the conversation away from the confines it looked like it was keeping to. The conversation jumps through discos and theatres and things, Strummer and Jones really wanting to go but. keep getting worked up by the questions. They have to answer. Who else will point these things out? Eventually the careful female voice asks for some final words of wisdom;

Jones: "Keep on complaining." Strummer scrawls TRUE on the wall behind Jones' head as he speaks. "If you want to give us a hand you've really got to do it... if you want to hear things on the radio you got to ring up the radio station..." .

Strummer: "In Detroit they've got a free radio organisation ...free radio for the '80s, they ain't being passive ... I'd just like to say don't be passive.."

Jones: "Don't be apathetic." .

Strummer: "And we highly recommed that you go'to a show and if you don't like the show you've got to bottle them off stage, yo,u gotta make your feelings felt. That way everybody knows what you want. If you don't tell anybody how they gonna know?"

OK. One more question can I ask: You're signed to CBS, and Columbia and all that stuff, are they trying to put any pressure'on you?

Jones: "They try."

Strummer: "We've been on Epic, we've been an artiste on Epic Records fortwo and a half years and for th'e first two and a half years they didn't even know we were on the label, and then they found out out and they come and shake our hands but they never makewith the chequebook baby. We want some • cheques, .otherwise how we gonna get petrol in the bus to get down to Kansas?"

Jones: "So come on. Hey this is on ABC not CBS!" —. ' •:• '

.Strummer: "CBS'hever come crawling..."

DETAILS: THE FANS

Don't ask-metobe your-hero I will only let you down

Don't ever sleep with your hero

Things will never be the same AH the beros, liike they say ,.

They're all dead out of the way,

If you see me on the street '

Don't attempt to speak to me, cos

If you see me on the street

I won't want to know you

— Patrik Fitzgerald. Copyright Control

explain to everybody that it's not worth it. In a situation like this it's better to keep signing. I just hope it doesn't do too much harm." Doesn't he see it as a sign he's achieving something I ask, as another autograph has to be signed?

Mick Jones likes the Patrik Fitzgerald song 'Your Hero.' He says that Fitzgerald has got it exactly right, which is odd'because Fitzgerald must never have experienced, perhaps only anticipated, what Jones has to go through ... as a new hero.

Even in America, walking down the street, visiting clubs/in the dressing room, teenagers and people in their twenties clamour around Jones, clutch his hand, offer bits of paper for autographs, attempt conversation ... Jones always seems a little unsure ...

"I find the laying of hands a very strange , thing. No one's come along and wanted to shake my hand in order to heal me, but they often look to be healed ..."

"Yeah, I know what you mean," agrees Strummer, "they want to shake your hand, but they want to take something, I don't know what..."

"They never offer anything, or very few do," continues Jones. Even so, Jones often looks for something.

After 20/20 have used The Clash, Jones and Strummer move back to the nearby dressing room, overflowing with New Yorkers. The previous night's New York performance had seen a post gig dressing room filled with slick liggers and empty smilers. For the second night, Jones wanted the fans to be let in.

The fans are let in. Stern but not impassive school teacher Kozmo Vinyl organises them in . batches. Jones never really knows how to handle them, but he wants the experierrce.

Jones back in the dressing room, fans move in for the kill. Jones, is, unusually, frowning. He's not pleased with the tv performance. He's not as comfortable as the others with Clash's tendency to lark about. "I think we were a bit like Morecambe and Wise," he mutters, "it's like a comedy. It wasn't right, what we're talking about isn't comedy, it's tragedy, the story is a tragedy. Still by the time they've fucking finished with it..." '

All the time Jones is talking to me in the crush of the dressing room he's obliged to sign autographs and put on a brave face through his fretting. "I can refuse, but I feel that I/need to explain why I am refusing. In the streets I refuse; it feels like a mutually humiliating experience. This is why now I'm talking to you I'm signing, it takes time to

"Not at all. If all we've achieved is someone wanting my autograph then I think we've gone wrong." ,

Jones seems in an emotional mood, a little pensive, so it is a good time to ask him what he wants to achieve. He looks into the distance, oblivious for the moment.to the congratulatory hubble and cry of New York's finest all round him and the people close to looking for a look. The grin has gone.

"What do I want to acheive ... I want things to be different here ... I want things to be different in England ... I want stupid things like ' people happy... and real music ... and an end to all the shit... I just feel to be able to contribute, that's an acheivement in itself. Change? Little things do change but it takes a bloody lot longer than people think. In away that's what I mean when I say there's too many smiles, because although I enjoy the playing I don't want people to think I'm all 'Ha ha ha how you doing let's boogie! 'y'know, cos that's no challenge for the audience, that's exactly what they're expecting, and then they get what they expect. Well I hope that we're gonna be something that they don't expect."

He emphasises the don't. People around are beginning to listen. I ask him about The Clash clowing. .

"I-think there's too much. I do want people to have a great time and enjoy themselves,-and I think that's what it's all abou.t really, as far as the concert is concerned right, but somehow I don't feel good unless I feel that they've gone away and thought about it or something ...the after effect, the aftertaste is what I'm really 'after."

A small bearded person nearby has been listening. He speaks: "I think everybody buys your record after the.show and they get the text."

Jones jsn't satisfied. "I don't want everybody to buy the record just because that's what you do after you've seen a group, although I do want people to have the records, but that like ain't the be all and end all of it, it's I'ike only the start when you've got the records. That's where it starts. You've got to hear it and really listen and then maybe there'll be a change. Maybe that'sjust my imagination ..." Jones is often very self depracating about his passion.

"Maybe there won't be a change. How does it affect you?" he asks the small bearded person. ' "

The small bearded person comes on like a university lecturer. "I can say that in Belgium there's a lot of people listening to these records and discussing about it, they're saying this, they're saying that, anti-capitilistic things, discussing starts it and then it goes further and further and it-starts to change your life, things other than things like money are important, saying everything's beautiful and I love you ...things to change."

Jones pulls a face: "Sounds like George Harrison to me."

"No," retorts the small bearded person, "I'm not an optimist."

"No, I agree with most of the things you say," says Jones, "We're living in the material world! Good old George! I'm going to join a monastry, Paul."

He's alright, I say. He has financed Life Of Brian.

Jones' grin twitches. "George Harrison is a good bloke after all! Hey look!" he lunges away and grabs a boy a couple of yards that he'd been talking to before. "Tell this guy what you were saying before about Bored With The USA and New York"

The boy drawls at me, with as much a garble as possible with such a slow accent. "They ' were bored with the USA until they came over here and realised that the fans loved them, realised that The Clash are the ones so we figured that yo,u weren't, bored with us no more and you wanted to come here, and then you play the songs ........... You've got to keep coming!

Jones is pleased that he is having a conversation with a fan that seems quite constructive. He's getting.information. He continues reliving the previous conversation they'd had. "What about if we started to sound a bit strange to you, playing all acoustic . numbers or something, what would you think of that?"

"That's ok."

"What about jazz?"

"Hang on, you said two things, before you just said acoustic ... acoustic work I like — 'Groovy Times', that is really special maaan .

"If we played jazz ..."

"Naaah ... I think we'd fade away a little."

"But they love us now," Jones smiles. T+ie future takes care of itself. -

"Aaaw I really love you now," the fan is a fan again. "It's not like The Ramones, they keep playing the same sound!"

"And we are always different!" triumphs Jones. The grin returns. For now at least.

Next Week: More Details — The Show: Before., During and After; The Interview, The Radio Show, The Experiencing, The Tedium And Where Will It End? — "You've got to think of it in terms of fifteen rounds. One or two people are finishing the fifteen. We've just finished the first round, but we had a big introduction,"

![]()

The Fastest Gang In The West (Part 2)

Details: PAUL MORLEY Photography: PENNIE SMITH

DETAILS: THE FIFTH MEMBER

Micky Gallagher turned up in Boston. Four or five dates into the Clash itinerary and The Blockheads' jumpy Irish keyboardist slips in to play, hanging about during daytime hours waiting to meet up with Clashmen who stay in bed late recovering from a 15-hour journey from Detroit. "I hated that, waiting around."

Gallagher has contributed keyboard sounds to the deeper, wider new clash songs, but knew little of The Clash from 'White Riot 'through to'I Fought The Law/ Only recently had he familiarised^ himself with Clash history.

His presence is part of the Clash growth process.

"\ never envisaged this kind of development' admits Strummer. "Mick said to me six months ago we'll get a piano player for the British tour and I said 'Oi leave it out, we're a four-piece group', and then we got Mickey down to play in the studio. Organ's so much cooler than piano!"

Visually Gallagher is an interference, musically superfluous, but he's a necessary experiment. And 'White Riot' or 'Garageland' with Gallagher frantically washing the rush riffs with organ swells has to be a 'Blonde On Blonde' on speed design. "Great, great, what a sound," drools Strummer, an unashamed rock historian.

"When I was on the plane coming over," confides Gallagher a couple of hours before the show, finding it diffucult to keep still, "I wondered what the hell I was doing. But then I realised it was too late, I had to get on with it. I get off on the nervous energy of the group, different kinds of energy. That'll get me through. There's Joe's energy and Mick's energy and Topper's energy and Paul I don't really know, he's a bit quiet. I'm looking forward to it." He attempts a smile. He can't keep still.

Gallagher and The Clash spend the Boston soundcheck getting used to each other; plenty of A's and B's and D minor's fly around as Gallagher within an hour attempts to become an integral part of the Clash slam. The night's show indicates no radical progression. Tucked away at the side of the stage, Gallagher is barely heard or seen. He chews gum feverishly and is kept on his feet. Just before going on stage, for the ninth song in the set, to play through to the encores — 19th or 20th — Gallagher seems to be edging towards the side door, a sick look on his face.

The first time Mickey Gallagher ever saw ~ The Clash live on stage he played with them.

DETAILS: THE INTERVIEW

Boston hours are split between absorbing Gallagher and squabbling about when to journey to New York for the next day's Palladium appearance. Initially Headon, Strummer and Simonon favour travelling immediately after the Boston gig, which will get them into New York by eight. Theoretically. Mick Jones dislikes the idea, preferring to leave Boston early in the morning. Ten to arrive at two. Clash aren't the world winners at early rising.

After much discussion Strummer and Headon come round to Jones' way of thinking. Simonon unfussily travels on the roadies' bus straight after the gig with his New York girl friend Debbie. The other three decide to sleep in Boston and leave early for New York — which ultimately sees them departing at midday, arriving at four and going right into the soundcheck.

Clash's journeys through America are on a silver thin coach, complete with i claustrophobic bunks, a toilet, a table, some cupboards, some seats, and plenty of rockabilly, reggae and Motown. It's not luxury travel, but it's a couple up on The Undertones' car and Gang Of Four's transit. With Kozmo Vinyl on board, parts of the journeys are something like parties.

There are a number of overnight journeys without hotels. Vast expanses of America are glimpsed brokenly through darkened windows; fleetingly, frustratingly. Forgotten, Bits of cities are seen at a distance. The mind strays behind the body. Is this a sacrifice? An adventure? A privelege?

"Well, we must always compare this poncing about with what they're doing back home," reasons Strummer. "Like say what my mates are doing, maybe working in a motorcycle shop, right? I mean we've either got to do that or do this as far as I'm concerned. There's no lying about on the beach ... if you have a.job—you've done a job, getting up and things—that's a pressure, and we don't have to do that. We have to do this instead. That's what we've got to compare it with. To take the rough with the smooth."

Strummer thinks a lot in these terms.

"It can turn round that you don't. It can happen. But having people like Koz along on a jaunt like this can help, especially if you're down ... he says things with that in mind, like say you go, oh no another five hours to Chicago, he'll go, well it's fucking better than?!!' and he'll describe someone working in a baker back in England or something. That helps me. You'll sniff and go bollocks ho hum, Detroit, or whatever, you'll slip — and you need someone to come along and go, you tosser, do you know where you are? And you go, that's right! All that childish sort of thrill is essential when you come over here. My God! We're going to New York! I hope I never lose that."

Coach journeys can be smooth enough and monotonous enough —time stands still — to be ideal places for tape recorded conversation. Insulated by circumstances, interviewees staring out the back of a coach at disappearing countryside become revealingly introverted.

Boston to New York; up the back of the coach sat by a crumpled Mick Jones who's sleeping off the genuine traumas of having to rise at 11 o'clock, Joe Strummer, looking preoccupied yet talking sharp, speaks his way towards Manhattan.

What you're doing/1 ask... it has to be done?

"Yeah. It has to be done. The same way that Koz talks about the radio airwaves, every second we're on the radio that's a second less Boston or Foreigner. In the same way I keep thinking of all those studios in London or Kingston Jamaica or anywhere, and you get a picture of London with like fifty recording studios and they're full with groups in the morning and groups in the afternoon, all those studios used by all those people-and I just think we gotta get in there arid grab some of that time.

"That's why I say it's gotta be done. If we don't some other group's gonna get in there, you know what I mean,-and we're egotistical enough to think we've got something to say. All those tape machines are waiting there for our big say."

Do you have to do it for yourself?

Strummer shrugs, he looks around, his mind seems to wander.

"I don't know. I'm not sure how I got to be here. I can't put no perspective on iL It hasn't happened that fast, we've been going for like three years and that's a long time, so I dunno., I can't quite figure out what it is that we do. Maybe we're so close up to it, the records-and the shows and the interviews, and I just can't see what it is that we are."

So what was the initial energy?

"I think it must be the hunger," concedes Strummer, seriously. "That thing, everyone says the best groups are the hungry groups, the ones that want a piece of the action, i think it was hunger to be heard, hunger to make your mark. Through Bernie Rhodes or Johnny Rotten or our own thinking, or a combination of those things we found something to write about; it's a strange thing to say but everybody needs something to write about.

"I remember what a fuck-up it was after the first record. We wrote all those songs, believed in them, dead sincerely, maybe . naively—you can listen to them now and maybe laugh at some of them, but after we'd done that we kind of turned round and said now what are we going to do?Wejust couldn't think of anything to follow it with really. We sat back and it was kind of yeah, and then it was what about the second LP? ' And we were kind of going, hey hang on a minute, and so we had to think about it for a '" long time. Eighteen months I think it took us."

It's taken The Clash this long to get over the force of that first LP; its reputation, its comparative completeness.

"After doing the second LP it almost killed us. Somehow all that business of flying over to America and like all the hours with Pearlman in the studio, it half killed us. We came out likezombies—and we looked at each other and we said we don't want to go through that again. We were really low at the beginning of this year, spiritually, really low. We'd just done a tour of Britain or somewhere, and we thought now is the time that we want to sit down and write a load of new songs, and throw all the bollocks out of the window, forge on new. -

"We went and retreated into Pimlico and we stayed there for a couple of months, writing everyday and recording..."

Mick had been talking a lot about'''ow the changes since the first album, the growing pains, the mistakes, had been done under public scrutiny: "washing out our dirty linen in public". Was this the first time since the opening period you've been able to work more or less privately?

• "Yeah, it was. In Pimlico we were all on our own. It was the only way we could survive."

Do you feel pressures? '

"I don't feel too many pressures at the moment but sometimes I feel pressure to bust. The number one pressure is coming up with it over the place. The Clash are growing up, potentially not a group for the squeamish.

Lyrically, there's a change too. Less a perverse, persistent journalistic parody, a commentary on surroundings, more a concentration on the nature of response. Mastering or reacting to events? Looking in, not out. Exploring.

"We're stepping into a few areas that we've left untouched, like sexuality. . .things like that, I dunno, urban psychosis . . .like plumbing the depths," Strummer tantalisingly explains.

"Depression," Jones sneers with a mixture of relish and distaste, "real depression, as opposed to being depressed cos you haven't got a job."

Confessional? Clash depression?

"It might be something to do with being in The Clash," Jones enunciates, "All of it actually, it's everything."

"It comes with pumping it out all the time," Strummer thinks, "and sometimes we don't get nothing back and we really get down."

Are you bothered how people are going to take it?

"Naah." Strummer dismisses the idea. "We're so far gone, I tell you. I feel I could get up and do anything really. Y'know, I'm way past al! that What are they going to think of this? I don't care anymore . . .cos whatever you do people are going to say bollocks — it doesn't matter what."

Clash are playing halls in America, and responses are good, sometimes too good. "New York is a Clash city, Chicago is a Clash city, Los Angeles is a Clash city, Boston is a Clash city. . . Detroit isn't but we're working on it."

Detroit is notoriously tough city. The audience is not particularly aggressive, just blank. The Clash sensed the negativity from the stage and grew progressively angry. They failed to finish the set. "We did what we had to do, we did our job." -"oorted that the response was, for

"No, I suggest that may be The ... the suspicious and the cynical, and be a little more patient.

"When a group gets in a bad mood it's in a bad mood," Strummer tells me. "To have a good night you've got to have a bad night, and like I was just in a bad mood. I don't know why . . . but it was such a comedown after playing Chicago, that was like playing Manchester or something like that. That's a bad mood to get into, I like to stay clear of it. It's really really » nasty: you're playing songs for people, pouring out your heart and your whole, but at the same time it's like schizophrenic, cos you hate them. It's really weird.

"I was pissed off because I'd been around all those radio stations in the morning" — every city The Clash visit Kozmo arranges radio interviews to noisily spread the message — "and I knew that as soon as we left them they'd been going. And here's the new one from Styx or Boston, er mommas going to lick you tonight. . ."

"We were getting out the Foriegner and Boston LPs at one of the stations we were at" —Jones rolls his eyes-—"scratching them and putting them back."

Strummer: "So they'd goto get their most played LPs and they'd say. Gee we don't have a copy."

Jones: "Or hopefully they'll not notice and play them . . . it'll get through quicker, it'll jump. We'll try anything ..."

"But I was feeling really hopeless," continues Strummer. "Those radio stations in Detroit — I knew that as soon as we drew out of the car park they'd be into the old Styx, And it just seems all the Epic guys that you meet across the country, they're kind of 'Yeah I rea I ly think you stuff's great' but they're wearing Meatloaf Jackets, and you realise Meatloaf, The Clash — it all means the same thing to them. The great grey people out there, it means the same thing to them. That really does get on top of me, the thought that people have no judgement.

"I was feeling angry about this and then the Detroit audience just sitting there didn't help. We've really got high standards. The British audiences that we've been brought up on have always been great and that's our high standards and if an audience doesn't reach that or if we can't get an audience up to that pitch, then we'll feel angry and we'll blame it on them. We'll take some of the blame, but we'll blame it on them too cos it's got to be both, hasn't it? And I can't stand it if they're just going well hit me babay. Like fat Rob Tyner sat in the front row, with his arms folded. Hit me. . .Yaah!"

"I gave him a look to melt him," grins Jones, referring to Tyner, another member of MC5. "The difference between that guy and Wayne Kramer! Kramer said before we went on. Don't ever pander to these people, really hit hard, and after the show he was the first one back to still be positive, and that's the difference."

"Audiences have got to help." Strummer won't let go. "They've got to get up and say,» Give it to me I'm ready for it. It's no use sitting back and saying. Impress me, cos if I feel that they're doing that I get really pissed off. That's when I start hating it, that's when it starts coming over really twisted."

3. AFTER. Following most shows Clash wound down in small hotel rooms with liquor and late night TV movies, or travelled to the next city. Detroit had to be different.

In a small club somewhere in the city Wayne Kramer, dressed like a bank clerk somehow managing to play crude jams with Johnny Thunders, falling over somehow managing to play sweet on Berry and Hendrix bar songs. The legends pile up on top of one another. Thunders and Kramer in a Detroit club!

Jones breaks out of himself. He's just finished his own show: "This is what its all about," he gushes, swaying at the front, loving it all, hardly believing it.

Once, on the coach, as Jones rolled yet another joint, I laughingly pointed out that here was the definitive Jones. He laughs a little but he suddenly realises what I mean and he's quite hurt. "No it's not," he insists. Of course, he's right. The defninitive Mick Jones is onstage, holding a guitar.

After Kramer and Thunders have licked each other, and Kramer has insulted me, Jones is first on the coach ready for the short journey back to the motel. As everyone else gathers he's wildly enthusing. "That was something special"

When a couple of manager type persons are in earshot he exclaims: "We've got to get them on a couple of American dates." Financial difficulties are pointed out. Jones is still on a high. "We've been privileged to see that, but how many people get the chance to got to a Detroit club? We've got to get them on the British tourl" It's carefully pointed out that this isn't as easy as it seems. The dream crumbles around him. Jones slips from his high. By the time the coach pulls up outside the hotel, he's totally quiet. Putting on a brave face.

DETAILS: THE WAY OUT

On the Boston to New York coach Mick Jones has surfaced from his deep slumber and has joined in the conversation. We're discussing how the old rock people let us down; how they didn't drag anything with them, how they abuse their position of power. They don't use their influence positively. Is it possible?

"I think it's because they're not bitter enough. We're really bitter enough."

Clash have it within their potential to be superstars. These words are realistic.

"Yeah, we're really bitter and no amount of sweetening will change that... I dunno, 1 just don't want them to get around us..."

Can they resist the effects that mellow out and isolate?

"Yeah. Our only hope lies in the fact that they've all been and done it. When we were in school we watched them do it, and so we've got one more dimension than they have. This ain't the '60s. Things are different, y'know, and we're a really different group than there used t0 be around. Things are changing and this is;

one of the aspects of the change. Y'know? I mean, should we really be here . . . ? We could've exploded already. . . gone on self-destruct in Guildford or Aberdeen ..."

"Those early dates?" asks Strummer. "Yeah."

"But we've got to go 15 rounds," emphasises Jones.

But is that it? Fifteen rounds and over?

Strummer thinks it over. "Well, you see, people think doing one round is it, but they don't realise that there's fucking 15 rounds! Look at the Stones—they're maybe on the 10th or 11th. Chuck Berry's on the 15th and maybe he's gonna come out for another bout. It's so quick in London, your 15 minutes of fame and then you're into the dumper. It's so quick people think that's all there is. But they don't realise that it's got to go on and on and it's no use counting up now." Strummer continually speaks in the sturdy language of the rock'n'roll traditionalist.

What round do you think you're on? Three or four?

"Actually I don't think that we've done three or four. . . maybe one. One round, come out, make yourself known, deliver your first punches."

Jones: "We had a big build-up..."

Strummer: "A long introduction! The band, silk dressing gowns. . . !" .

Are you looking forward to the day you can wave bye bye to CBS?

/'I never realised when we got signed up—alright, here's your advance—I never realised it'd all go on touring, and I never realised that it would go click like that. You have to realise that you need to work for fucking years . . . people say to us. What are you going to do with your dough? What they don't realise is that it's going to take a few more years of slogging..."

Jones: "An advance means that we owe it. It's a loan. Record companies are like a bank..."

"I'm looking forward to the day the CBS contract runs out," Strummer understates, "although I don't think you can regret anything."

Do you feel comfortable talking in terms of slogging away j for years, of entering the routine of album, tour, album, tour, the gaps getting longer?

"I dunno. I was thinking last night of the theatre—imagine you're an actor. Every night you go on and do the same thing, you're in the same play for weeks, that means every night except for Sundays you're going to go through the motions while loads of different people watch, and going to - bed and waking up is the refreshment in order to be able to do that every night. It seems to me to be the same making a record. You make one, and you've got to forget all about it completely and then you make a new record and it seems like a new thing and then you forget all about that and when you come to make the next record it all seems to be new. I think there's enough time so it doesn't seem like routine. I enjoy making records, I enjoy doing shows. I don't know what else we can do . . ."

DETAILS: THE CLASH

"Well, I tell you," asserts Mick Jones, "if I wasn't in The Clash I would definitely have their records. The Clash is everything to me. I have nothing else... I'm under the impression that I have given up everything else for it, I'm under the impression that I have lost everything. It's my own personal dilemma."

You've lost everything?

"Everything. Home, personal life. . . everything. So my dilemma is in a way that I resent The Clash . . ."

Is this what depresses you?

"That and the world in general. Life itself depresses me. Naah, it's not too bad really. . . what did Woody Alien say?. You should be happy to be miserable because if you're miserable you're better off than some."

Would you try arid bland yourself out, become less intense?

"Never. I wouldn't allow myself to bland out. To be bland. I don't mind being obnoxious or depressed but never bland. Maybe on my own, actually, but when I'm out I refuse to be bland, I wanna feel... I wanna know what it's like."

It? .

"Life. To live. It sounds like Hemingway! We should go to Africa."

DETAILS: THE END

Paul Simenon enters through the back door of the New York Palladium and limps towards the front of the stage, which is being prepared by roadies and technicians for a soundcheck.

He stares out into the lifeless auditorium, sized and shaped like a British Apollo or Odeon, maybe a little steeper. He shakes his head at all the empty seats, thinks ahead to when they'll all be filled;

"I don't know why they bother to come," he smiles shyly, and hobbles off towards the dressing-room.