Pearl Harbour Tour supported by Bo Diddley & The Cramps

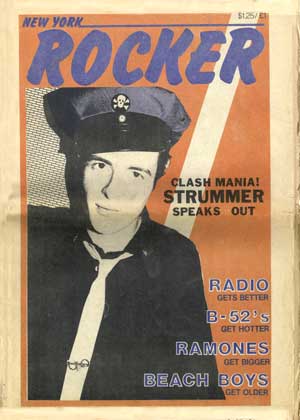

The New York Rocker - March 1979

Page 6

New York Palladium

Don't expect the back-Clash to start here. Since the Clash's smashingly successful Palladium debut, I have had some second thoughts, but none of these contradict my first impression that this is the finest young rock 'n' roll unit in the world. Their performance still resonates, dominating my hopes and fears about the future of not only rock 'n' roll, but the world.

The critical reaction to the Clash was almost unanimously favorable, keyed by the frequent reference to the too-frightening-to-comprehend coincidence of China's invasion of Vietnam on the very night o( the show. The apocalyptic international situation was seemingly mirrored in the dramatic desperation of Joe Strummer's vibrating, vein-popping vocals and Mick Jones' dedication of "Hate and War" to the Red Menace.

The Clash's act was not only the epitome of an exciting rock 'n' roll show; it served as the climax of a 25-year era of peace, prosperity and a booming entertainment industry. The Clash shook and rumbled like the giant atomic generator in The China Syndrome; working at 110% capacity, they threatened to explode and take half the world with them.

In the aftermath, I've found that not everyone was left as "slackjawed" and awed as I was by the concert. The first group to express disappointment all share a distinctively similar trait: they're women. I cannot be too surprised at this, since a large part of the Clash's appeal lies in adolescent and post-adolescent fantasies which seem to me overwhelmingly male in character.

The Clash are about the extended, male-bonded family of the street gang, just as films like The Warriors and The Deer Hunter are. Like Michael Cimino's celebrated screen epic of the Vietnam War, the Clash react to our indirect experience of that war through the media—by creating through that same media an artificial situation of danger that aesthetically mines the crisis conditions of wartime.

While drawing on the real-life chaos and wanton destruction that nightly dominate the evening news, the Clash (like TV itself) bring global conflict into our heretofore safe living rooms.

Similarly, the recurring "Russian roulette" metaphor in The Deer Hunter emphasizes man's existential need to intensify his life by courting death. Which leads to the other major philosophical complaint I've heard about the Clash: that their revolutionary political stance is merely rhetoric or (worse yet) a commercial ploy.

They argue that the Clash herald and evoke the apocalypse only because, without its imminent arrival, the band loses much of its dramatic clout—like the prophet judged a kook because the end isn't really as near as he says it is. The band's glamorization of confrontational politics, their urgent romanticization of conflict, can only be clearly understood within the context of a post-Baby Boom generation which has, by and large, never experienced the brutality of war firsthand; I say, better the young should play in rock bands than fight World War, III.

In The Deer Hunter, Meryl Streep plays a smalltown girl/woman whose boyfriend never returns from Vietnam. Her sullen, mournful countenance blankly registers the toll of human loss incurred by,the absurd horrors of Southeast Asia.

Likewise, 'the individual members of the Clash are naively idealistic in a way that makes it impossible to question their motives. "Stay Free," a comparative clinker on Give 'Em Enough Rope, becomes a delightful paean to lost innocence on stage, with Mick Jones' vocal a touching tribute to times irrevocably gone, but not forgotten. The Clash are anything but belligerent warmongers and troublemakers, even if that has often been their public pose.

Co leaders Joe Strum-mer and Mick Jones are a rare creative pair: they are perfect complements to one another, equalling more together than the sum of their two personalities would have you believe. A defect in one is uncannily balanced by a corresponding strength inline other.

Upon meeting the band, I was immediately attracted to Strummer (nee Gregory Mellor) while my colleague Alan Platt took to the flashy Mick, a/k/a Michael Jones. Strummer looked me straigrit in the eye as he patiently articulated afpofnt, often touching my arm lightly for emphasis.

I thought Joe represented the Clash's soul-in-conflict, a romantic idealist to be ultimately consumed by his torments. Strummer is the typical Jewish intellectual in rock 'n' roll terms, passionately torn between the dictates of his head and his heart, who can't relax if he thinks there's anyone out there suffering, I can easily understand how hardcore rockers would be more easily drawn to lead guitarist Jonesy, as much the musical spirit of the Clash as Keith Richard is of the Stones: cocky, arrogant and quick-witted, yet at the

same time sensitive, vulnerable and shy. It surprised me to shake their hands; they seemed small and frail,remarkably free of callouses and toughness, almost feminine. I really liked both men, though the record company-controlled interview setting (at a fancy mid-town Indian restaurant) was hardly a normal, everyday conversational situation.

The Clash's brand of hard rock is certainly not new, though the speed and intensity with which it is played is the artistic culmination of rock's first 25 years. Another bunch of Clash-baiters must include those who claim they never liked the band's most obvious progenitors the Who, and by extension any British rock 'n' roll which tampers-with Chuck Berry's hallowed riffs.

In fact, a coterie of reactionary, purist rockers (reacting, perhaps, to the most distasteful and stupid excesses of the British punk scene) are saying that modern-day English rock 'n' roll is somehow a degeneration of the Real Thing, the American Sound. Ironically, this is the same sensibility which informed the Clash's own choice of Bo Diddley as their support act.

The Clash represent everything that has always been refreshing about English bands, who consistently manage to bring a fervor, joy, and passion to rock 'n' roll that goes unmatched here in the birthplace of the music. In class-conscious Great Britain there is an unswaying belief—rekindled by the new wave—in rock 'n' roll culture as a way of life, a way out of either the ghetto or the suburbs; it's a point of view that has never really taken hold in "upwardly mobile" America.

Add to this the uniquely English eccentricity of perspective, a Continental sense of modern fashion and style, a music-hall legacy of showmanship, a European tradition of progressive political thought and post-war sense of urgency and you have a potent combination sadly lacking in all but a few current American acts.

Of course, the Clash are only a rock 'n' roll band, and their show in February only a dramatic performance, even if fraught with very real tension and catharsis. And yet," these four young Englishmen managed to touch on a raw nerve of conflict and friction—the fact that when violence erupts, it touches everyone, especially those comfortably watching it on the tube. The greatest rock experiences manage that, but for a brief moment this band tied the whole damn cosmos together with a power chord that blew off with a bang, not just an overhyped whimper.

The Clash are stars. The stars are matter; We are matter. It doesn't matter. Fora little over an hour, the Clash previewed the world war which will destroy us all. Luckily, we're still here to ponder the implications. I haven't been the same since.

by Roy Trakin