Pearl Harbour Tour supported by The Rentals & Bo Diddley

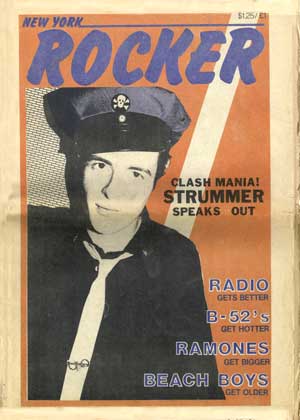

The New York Rocker - March 1979

The New York Rocker - March 1979

Page 6

Boston

I've always estimated Boston's punk rockers—Cantones regulars and the like—to number about 400. But 1600-persons, about half of them garbed as punks, attended the Clash concert at Harvard Square Theater. I saw many curious hippies, a squad or two of political radicals, and a main floor bloc of musicians, writers, photographers and record industrioids. A big sister brought her two little brothers, ages 13 and 15. She was the crowd's hero:

At least two mouths are likely spreading the news in junior high classrooms.

When the Clash finally stalked on to the dim stage, at least 400 persons pushed en masse to the rim of the orchestra pit, obscuring the seats. Before the lights came on, my friends and I had made it from row 24 to 8. The band blasted into "I'm So Bored with the U..S.A." A strange tingle overcame me, even though no drug other than coffee and nicotine coursed my veins, and I leaned against nearby bodies, exhilarated to be part of that seething throng of throbbing flesh. The'band followed with a raging "Guns On the Roof," and the tingle became a tremor. Images of Iranian street battles loomed in mind. At that moment, I tasted the thrill and terror of revolutionaries about to topple a Shah.

Over my shoulder, I saw a mass of thrashing fists in the air. The mob at stage front was ecstatic, perhaps tempted to trash the theater out of sheer exuberance. Those in the balcony and back rows, however, were subdued—curious and amused, but in complete control. Many in the back later complained of shoddy sound.

But a purpose, a call to action, united the reckless front ranks. Guitarist Mick Jones summed up the purpose when he pointed at the boiling mass and. screamed, "Get off your asses, you fuckin' lazy sods!" Of course, Jones was merely restating, in modern terms, rock 'n' roll's primary dictum "Boogie!", a repugnant word in these post-hippie days. But this restatement of ideals is much of the value we hear in punk. The Clash make good punk's promise that rock 'n' roll can still evoke untamed passion in the modern world.

The opening songs affirmed the rumor that the band didn't have time for a sound check. Strummer's mike kept blipping on and off. Simonon's bass often droned weakly. But the band, tapping energy in spite of the snafus, threw the front rows into frenzy. Five songs later, when Nicky Headon fired oft his hot lead snare beats at the beginning of "Tomnay Gun," my ears went numb. The fall of Khe Sanh couldn't have been louder.

An unpretentious drummer, Headon's beats fell sparsely, a wide gap between each. His snare drum resounded like evenly-spaced rifle shots. Unlike his mates, he fought fair, never straying from the beat, and rarely taking chances. His effortless rhythms anchored the music. Paul Simonon's bass, on the other hand, was a creature seeking escape. He could barely restrain it. His long strides about stage fell heavily and he ripped furiously at the strings. The instument flew from him, but with arms and hands blurring, he would wrench it back from the air and resume pounding. Jones's lead guitar lines chewed into the din. Sometimes (in "Stay Free," for example) he injected delicate leads. After the line "I practice this thing in my room" (I think that's what he said), his guitar spilled a dozen soft notes that floated in the barrage.

But Joe Strummer fronted most of the show. His palpable air of anger and frustration makes him appear permanently on the edge of a nervous breakdown. In spite of his venom and broken tooth snarling howl, there is an enormous gob of compassion in Strummer. Early in the show, he pointed at the empty orchestra pit in front of the stage and complained of the gulf it put between the band and their fans. For each volley of hatred he fired, Strummer usually followed with a gesture of affection, such as a smile at a rambunctious fan. He often left the center stage to Jones and Simonon (once even pulling Jones by the shirt sleeve towards the middle mike) and confronted the stoic Headon with a series of funny faces.

After 22 songs, including four in the encore, the unruly mob finally calmed. They had experienced an intimate show and then suffered a certain melancholy at its end. The show touched me personally; except for Headon, I looked each band member in the eye at least once.

But it would be inaccurate riot to report that everyone I spoke with in the back rows and balcony felt a distance from the band. The passion didn't permeate the hall. The Clash, now in their prime, pro-jected to a front-row club. The farther back you were, the weaker the impact. At least 400 persons, however, were gripped by the world's most important rock 'n' roll band. Instinct tells me that number is now too conservative. I credit the Clash with swelling the ranks of Boston's rock 'n' roll core. In my mind, their concert surpassed the three best shows I've ever seen: the Rolling Stones, the Who and the Ramones.

by Doug Simmons