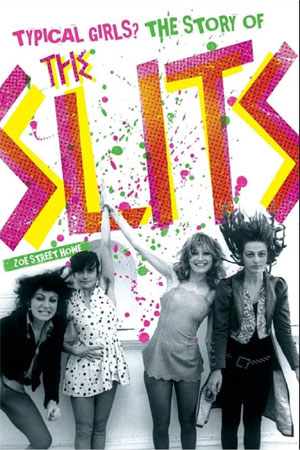

Typical Girls? The Story of the Slits

Typical Girls? The Story of the Slits

Chapter 5 White Riot Tour

May 1 rolled around and the month-long White Riot tour began, kicking off at Guildford's Civic Hall. In the same month X Ray Spex appeared at the first major Rock Against Racism gig. It was an important time for making a stand and ensuring a high-profile chasm between punk rock and prejudice.

The White Riot tour, which would later be described by journalist Jon Savage as the "last great punk rock tour", was funded entirely by The Clash, and this was typical of their philanthropic stance when it came to supporting up-and- coming groups, a stance now immortalised in Strummer's posthumous music charity Strummerville.

The Jam also joined the line-up, but soon turned on their Cuban heels after falling out with Bernie Rhodes. The Slits were not particularly bothered by The Jam's absence: to Viv at least, Paul Weller was disappointingly old-fashioned at the time. "Someone introduced me and said, ‘She's a guitarist' and he'd say, ‘Oh yeah, we could do with some crumpet in our band.'

"It's funny, he's seen as such a sensitive musician but there were very old-school types within the scene as well." After experiencing respect and a sense of equal footing among most of her punk peers, Weller's comment seemed rather unevolved. But The Slits had bigger things to concern them.

The Palmolive-penned ‘Number One Enemy' seemed to be a self-fulfilling prophecy, in the eyes of the public at least. Because they stood out from the crowd the early punks in London and elsewhere were often looked upon with distaste and treated with caution, or aggression, but The Slits, being girls, were regarded as particularly dangerous and unpredictable. This was partly because they were unpredictable, but a myriad of deeply ingrained Seventies prejudices didn't help their cause. Palmolive at the time admitted her strength and power on the drums came from "thinking of people that I hate" - and there were understandably no shortage of candidates.

Still, the prospects for this particular tour were somewhat more promising than those of The Sex Pistols' earlier Anarchy tour, much of which had been abandoned, and the vibe was lighter, like a "school trip", as Tessa remembers. "It was St Trinian's meets the Bash Street Boys," she says. "Punk was like being caught in a comic." But it was hard work too - every single night they played a gig, and the tour took them everywhere from the Edinburgh Playhouse to the De Montfort Hall in Leicester to the California Ballroom, Dunstable. They even squeezed in a date at the Brakke Grand in Amsterdam.

Buzzcocks' Pete Shelley told Pat Gilbert: "(White Riot) was the first proper road show. The Anarchy tour hadn't managed to do that. Its notoriety went ahead of it like a leper's bell. The Clash played everywhere with The Slits, Subway Sect and us. It was great, it was actually working."

What helped it work, from The Slits' point of view, was the fact that the male punk groups continued to be very supportive of them. It wasn't just an initial show of kindness that wore off once the ‘girl band' novelty had dissolved. Despite help from Don and Nora, for the first few years of the punk revolution, The Slits felt largely alone - but it would be friendships with The Clash, Buzzcocks and many other groups that got them through.

Ari: "From 1976-78, we were wheeling and dealing, doing all our own shit basically, without the help of the industry. The only support we had was from our guy friends who were all in groups, all of our peers like The Clash and Pistols and other groups like Eater and Subway Sect, Slaughter & The Dogs, Buzzcocks of course.

"People like Siouxsie & The Banshees, X Ray Spex, Adverts, Talking Heads, they were the only other bands that had girls in them, punk girls with the same type of vibe: ‘Fuck everything, I can't relate to anyone, no one in my family, none of my friends, none of my future, none of my past, got no one to look up to. I'm just going to believe in me and do my own stuff and jump on the stage'."

All in all, on this tour, it was working, but it was hard work - The Slits were hard work, between themselves and for other people. Personalities on tour are always magnified and every moment, positive or negative, is more intense. It was easy to feel lonely sometimes, even within the bosom of the punk family.

Viv: "Tessa was very close to Palmolive, she and Palmolive were a bit like naughty girls together. Palmolive was the outgoing one and Tessa was the sort of sidekick. It was a bit excluding, you know, band dynamics and all that. And Tessa was very quiet, always known as ‘the quiet one' - it was probably a couple of years before we had a proper conversation or I saw her cry or anything.

"So there was the bass and drums dynamic, and then there was Ari on her own, completely confident and doing her own thing, and me on my own. So me and Ari were both on our own, but Ari didn't mind."

One mutual foe they could easily unite against was the rest of the world, most notably the (generally) thick, scared and bigoted red-top-reading public, and it has gone down in punk folklore that on the White Riot tour itself The Slits became officially enshrined as public enemy number one. Depending on one's point of view it was a fantastic compliment, but it served to make life difficult for them, and for the man who was supposed to be smoothing the way, Don Letts, who was "mismanaging them", as he often quips, at the time.

Most hotels banned the girls on sight, and then rang all of the other hotels in the area to ensure no others took in these terrifying liabilities either. Tessa remembers arriving at one hotel and, just because she had ‘The Slits' graffitied on her guitar case, they were thrown out immediately. The provocative name was enough, and that notoriety was flaring up angrily wherever this lawless girl band happened to be.

Stories of friction between the tour-bus driver, Norman, and the girls, Ari in particular, are legendary. Confronted with the loud-mouthed, free-spirited and generally scantily clad 15-year-old, he decided he would lay down the law and simply not let The Slits on the bus. Never mind The Clash or Subway Sect - these bright, attractive, confusing young women were far more of a threat.

The Slits, therefore, were unable to even board the tour bus unless Don bribed Norman, which he did on a daily basis, but the uptight driver still made it very clear he couldn't bear them. They would turn up in tiny micro-skirts, slashed-up tops and fishnets, and to make matters worse Ari was working on those dreads, which at this early stage resembled an unwashed, matted bird's nest. These were definitely not the sort of girls a man of Norman's conservative outlook had ever encountered before, and every move they made wound him up. All this aggro, and they hadn't even played any tour dates yet.

"People didn't do this to The Clash, nor Buzzcocks, nor Subway Sect - just us," says Viv. "It was like apartheid. Ari would be shouting and laughing too loud and singing, and Norman couldn't stand it, it would make him cringe, he couldn't stand this young woman showing all her legs and half her arse, shouting and laughing and enjoying herself on the bus.

"She was dressed like you wouldn't have minded fucking her, he just couldn't stand it, that's what it was... that dichotomy of ‘you want to fuck them, and you want to kill them'."

The Clash and Subway Sect didn't need to be bribed (neither would Buzzcocks, but they were travelling separately) and the shabby treatment from Norman and Normankind simply made the boys on the tour more protective of the girls. Joe Strummer memorably substituted the lyric ‘What a liar' for ‘What a Norman' during The Clash's song ‘Deny' at their Leicester gig. Never mind gender differences, they saw Norman and his like as the enemy and The Slits as equals. They never lost sight of the fact they were girls too - but no one got "corrupted".

"The Clash were real boys," remembers Viv. "I don't think they ever saw us as not girls, there was always that there, especially as I was going out with Mick and Palmolive had been with Joe, and Paul [Simonon] was quite sexually aware, not that I'm saying he wanted to do anything but there was always an awareness of boys and girls.

"Ari was at school at the very beginning. Would I let my daughter be in a proper band and go on tour at that age? No way! But Ari didn't get corrupted, it was such a strict ethos, people weren't into screwing, it wasn't a shag-fest. Punks weren't into that particularly. There were always one or two, but people at the top like Malcolm McLaren or Johnny Rotten were asexual in a way. You had your Steve Joneses of course, it was written all over him what he was about!

"We weren't treated like ladettes like it is now but there was a respect without any problem, and an appreciation. I'm sure they didn't think we were anything as good as them, but they never said it and it was cool."

Another soon-to-be bosom pal and honorary ‘boy-Slit' was future Frankie Goes To Hollywood star Paul Rutherford, who first saw The Slits when the White Riot tour hit Manchester's Electric Circus on May 8. They were playing the set they had first unleashed on Harlesden in March, which included ‘Drug Town', ‘Slime', ‘Vindictive' and ‘Vaseline'. Their ability was still on the rough side, but that didn't seem to put anyone off, least of all Paul. "That was the first time they'd played up north, and I just fell completely in love with them. I thought they were amazing, they were the best band of the night," says Paul.

"I was in The Spitfire Boys at that time, and when they later got their first gig just as themselves up north in Eric's in Liverpool, we got support as we were the only Liverpool punk band at the time. I'd come down to London to see them too and we became great friends, I was just in love with every one of them. They were really doing something. To me they were the biggest band in the world, still are." The Slits were just as fond of The Spitfire Boys, and were a vital support to them when audiences were scant or they had nowhere to sleep.

"We were playing a gig at The Rock Garden in Covent Garden, and The Slits came down to hang out," says Budgie, Spitfire Boys' drummer and a future Slit (and Banshee) himself. "There was nobody else there. We were really privileged to have The Slits in our audience because they were the only audience!

"I remember crashing at Ari's mum's place. There was a bit of fan-worship from Paul to Ari, and we were lucky to have a place to stay, we thought it was really cool. The really exciting part, coming from where we came from, was that suddenly you had this thread right to the centre of the London movement - Malcolm, Bernie Rhodes, later Nils Stevenson, the Banshees manager. The Banshees were an enigma, and so were The Slits, but if you were in the camp you were like a little gang."

The Slits were very appreciative of the friendship of their like-minded male counterparts, and the boys were equally grateful for the girls' time, interest and generosity. There was a healthy dose of awe thrown in too. And while on tour, their pals might have developed the odd crush, but they were respected as a group, not treated as dolly birds.

Don remembers, "Everyone on the scene liked The Slits. For a start it was four girls, and when you're on the road with a load of ugly geezers, any female is a delight, as long as she's feminine, and it can't be denied, those girls cut a fine form.

"I mean, we were young guys, let's be honest, we were teenagers. I mean, what the fuck? So there's all that going on. But primarily they were respected as The Slits the band. They weren't sexual objects, but obviously being female made it that much easier to get through the door."

Well, that particular door anyway. There were plenty of other doors that would be slammed in their faces for the same reason. But at least on tour they were among friends (and Norman). Rivalry wasn't as much a problem in the punk scene as it could be in other movements, as they were all in the same boat; it was more of a mutual support network than a dog-eat-dog minefield.

Don adds, "When you're young you move in circles of literal gangs or metaphorical gangs of like-minded people, but I don't remember any specific rivalry between bands - they were all distinctly different, they weren't really treading on anybody's turf. Because there were different wings to this movement...well, a movement can't be a movement with just one band. They all sort of needed each other so it could be a bona fide movement."

The cause aside, this was also a bunch of creative, funny teens having a ball. There were pillow fights, spontaneous jam sessions. Mick Jones would help to tune the girls' guitars, and the journeys between towns had that constant soundtrack of Don's mix-tapes. They were like an excited bunch of big kids. At one point while stopping for petrol, Don filmed a woman flying into a rage just because Topper [Headon, Clash drummer], Paul and Clash crony Robin Banks were bouncing up and down on a see-saw to pass the time.

After hooking up with Buzzcocks at the various venues, they'd settle in before the gig. On occasion would there be the odd cat fight, as Don remembers, or an alpha-male dispute in the green room, but generally nothing too dramatic. Buzzcocks guitarist Steve Diggle and Mick Jones initially regarded each other with grumpy suspicion before becoming the best of pals. "I'd much rather have been in The Clash anyway," admits Steve.

To many, particularly the justifiably angry feminists of the Seventies, the fact that The Slits were actually included in this tour, and making a lot of noise while they were at it, was to be taken very seriously. They were having fun and doing what they wanted. Many women were not even remotely having fun or doing what they wanted - they were either housewives or doing jobs they didn't like or that didn't stretch or inspire them, or they were despairing of a future that looked all too similar.

The Slits weren't particularly interested in Women's Lib, and their approach was ultimately more successful and less eroding on themselves: don't get angry, don't think about chauvinists, get on with what you want to do and as long as you don't think they have any power over you, they won't.

Ari explains: "We weren't political, we weren't feminists by label, but we were automatically women's rights by being who we were and making sure we were who we were and remaining who we were. Punk really started with equality of girls. There's a whole culture - the first looks of so-called punk, so many girls contributed to that. And of course Vivienne Westwood, there was a window for female expression in punk when it started. That's why The Slits were even able to survive and live it, and be born into that revolution and have a chance. Windows were opening for them, even like the fanzines - the first punk fanzines were made by girls."

This was also the case for female music writers, not just on fanzines but in the hitherto male-dominated world of weekly music magazines - NME, Melody Maker and Sounds - that catered to fans whose interest lay beyond chart fodder, be it punk or prog or all things in between. It wasn't easy, in fact it was very hard to get through unless you were quite tough and prepared to "outman the men, like Barbara Charone", as Vivien Goldman observes. But the opportunity was there if you were prepared to grab it and make the best of it without letting sexism get under your skin.

Vivien explains, "I can definitely say that the arrival of punk made people like me and Caroline (Coon) feel a lot less alone, that for the first time we could really be part of a community instead of being one of the lads, but not really one of the lads.

"I don't think you're wrong when you see that conflict, I don't think you're being paranoid. But you can't live in a state of siege. You just have to have a light laugh and not be surprised. If you let it define your reactions, of course sometimes you have a wobble and it does, but generally you can't. You lose your wholeness and you're coming from a place of negative response to a bad vibe instead of coming wholly from your centre."

As Jolt fanzine editor Lucy Toothpaste told Jon Savage in his book England's Dreaming: "I never got one punk woman in any of my interviews to say she was a feminist, because I think they thought the feminist label was too worthy. But the lyrics they were coming up with were very challenging, questioning the messages we'd been fed thru Jackie comics."

Writer and artist Caroline Coon, who spent time with The Slits on the White Riot tour and went on to manage The Clash, witnessed a fresh approach when she questioned The Slits on ‘the Feminist Question'. The response was fiery, humorous, impatient and liberated in its sheer nonchalance.

She eulogised in Melody Maker: "The Slits are driving a coach and various guitars straight through a cornerstone of society - the concept of The Family and female domesticity - not, I hasten to add, that The Slits themselves will have anything to do with the Feminist Question ... While Ari groans at the very mention of the female gender, Viv warns me off.

‘"All that chauvinism stuff doesn't matter a fuck to us. You either think chauvinism is shit or you don't. We think it's shit ... Girls shouldn't hang around with people who give them aggro about what they want to do. If they do they're idiots.'"

If only they had a pound for every assumption they must have been militant bra-burning feminists. An all-girl group is an all-girl group - an all-boy group is just a group. And an all-girl group that isn't demure, wistful and sporting the same frocks and hairdos like some Phil Spector concoction is definitely to be treated with suspicion. Even when people with good intentions said their ‘hurrahs' for ‘Women in Rock', this still went a long way to shoving said women into a pigeonhole. No one referred to ‘Men in Rock'.

NME responded to a well-meaning reader request in 1976 that they do a ‘Women in Rock' feature with the spiky riposte: "Great thinking - when we've done that we could follow it up with ‘Black People of Rock, Jews of Rock, Blue- eyed People of Rock, Short People of Rock and achieve true liberation by categorising everybody in the world according to their gender, race, religion, colour, pigmentation or height. Let's get together and split up."

It remains a problem that any female in the music industry is lumped into the ‘Women in Rock' category, something that The Raincoats and The Slits can appreciate more now, but at the time it was frustrating, simply because, other than sharing a gender, the groups were very different indeed.

Ana da Silva: "It's to do with people's character. I can't go onstage and be Ari because I'm not Ari, I didn't want to be Ari. I'm who I am, and that was the thing with The Slits, they were all very different people. Tessa's very quiet but she's amazing on stage, she looks so tough, and just as interesting as anybody else.

"They gave something, we gave something different, and that's why we didn't like to be all together, always the ‘girl bands'. In retrospect we think it was more positive than that, but we didn't like to be seen as ‘a girl band', we wanted to be seen as a band that writes these kind of songs, that plays like this on stage, that do this way of recording, all the different aspects of being in a band, we wanted that to be seen as something that was The Raincoats, and The Slits were The Slits.

"We didn't want to be in the papers only if there was an article on ‘Women In Rock', that got on our nerves."

This form of ‘acceptance' was often a barrier of its own kind that was difficult to ignore, and left The Slits in particular struggling to shake off any association with feminism in its more political, militant sense. They knew it wasn't going to do them any favours, and it wasn't where they were coming from.

Keith Levene: "I think it's better they didn't push the feminist side of things because it's in your face anyway, you don't need to do that. It goes without saying. If you do start saying it, you can fuck up a whole other aspect that you might miss out on, and then there's the whole ‘Oh poxy feminists, who gives a fuck?' you know? Not me, but some observers might think like that.

"It was weird, the punk thing. It mattered that they were girls, but it really mattered that it didn't matter that they were girls. It matters they were there. You had a few firsts going on."

Where The Slits stood in the great feminist debate was the last thing on Don Letts' mind; he was more concerned about transporting them from A to B without getting a serious headache. He was at his wit's end trying to keep everything under control, but once he got them on the bus and on the road, he was damned if he could get them into hotels. The determined young manager was using money from his latest Chelsea retail experiment. Boy, to fund The Slits. Their manager-band relationship was only six weeks long, but what a six weeks.

"Touring with The Slits, that was a trip. It was chaos," says Don. "Punk was a social pariah, wherever you went the spotlight was on you, and it would bring out all of the people who were anti-punk, but it would also bring out a lot of people who just wanted to jump on the bandwagon, who didn't really have any ideology.

"It was potential madness. In fact it was guaranteed. Doing anything with The Slits was madness, you didn't have to be on tour! Just going down the street with them was mayhem. Ari was like a whirlwind, still is.

"Sometimes they'd be fighting before, during and after the gig. Entertaining for onlookers but for me it was a total pain in the arse. I remember them always having a go at Tessa for some reason. But I have to say that when they hit the stage, they really brought their shit together. And they weren't just The Slits on stage, they were The Slits 24/7, it wasn't an act.

"I remember trying to get them signed in to a hotel and Ari was behind me wrecking the place before we'd actually got signed in, so of course they'd then say, ‘We can't have you here.' It was a really hard time. I remember checking out of a hotel and I hear the hotel manager giving us a bill, and it was for like, drinks, food, dinner, and then I heard ‘One door' - and I was like, ‘There's a bill for a door?' and he said, ‘Yes, there's a door missing'.

"It was fun too, I ain't complaining, but at the end of the tour I remember standing at the back of the hall next to Bernie Rhodes, manager of The Clash, and I looked at him, and I looked at The Clash, and I thought, ‘I don't want to be this side of the fence, I don't want to be a manager any more.' Maybe if I'd have tried to stay their manager we wouldn't have been friends any more."

Indeed, friendships and futures were at stake all round where punk was concerned. Beneath the fearsome image lay discipline and passion, and anyone who lacked it, in the case of The Slits at least, was in danger of being left behind.

"I almost didn't make it to the White Riot tour," chuckles Tessa. "We were all rehearsing in the basement of this squat in Angel, I was having an off day and I'd taken a pill someone had offered me. I started to rehearse and then I got in a mood and threw the bass down and walked out. And you can see on Don Letts' Punk Rock Movie everyone's going, ‘Tessa's useless, we bought her equipment, we did this for her, we did that, why can't she get her shit together?'

"I knew they were just about to throw me out of the group, so every single day after that I was in the basement practising the bass! Ari wanted me to stay in the group and I was determined to make up for my ways and pulled myself together.

"It was real fun, the White Riot tour, Subway Sect were one of my favourite groups at the time. Your playing gets better when you go on tour, it's good for your musicianship."

Life on the road was heady - and while the band generally lived healthily and avoided drinking too much, their high- octane personalities and general defiance ensured an unforgettable trip. They were also showered with more spit than they ever thought possible (there was much finger- pointing as to who started off this almost universally unpopular punk tradition - some say the Pistols, some say The Damned - all say they hated it, although this clearly didn't transmit to the enthusiastic gobbers in the audience).

Thankfully, the spitting wouldn't last forever. A few years down the line The Slits would find themselves being pelted with roses (as well as phlegm) on the promotional tour for their first album, Cut, particularly in Italy. Which is a bit more civilised. But right now, The Slits felt it was way too early to be making their own records. While they were writing songs all the time, they knew how raw they were, and they were serious about getting their songs just right before they rushed into the studio. Good decision.

As we know, there was at least one couple on board the bus, and tensions ran high when Viv started to get close to Subway Sect guitarist Rob Marche. According to Viv some "unpleasant scenes" ensued between her and Mick Jones as a result. What's more, Palmolive had just split up with Joe Strummer, which led to a month and a half of the pair trying to avoid each other while on the same bus. Love and romance? It was never that simple.

"The White Riot tour was awful for me," admits Palmolive. "I'd just broken up with Joe, so I did not like that. It was a mutual thing, but it was still hard. In the van it wasn't too great. I don't remember it being a fun trip but you find other people to talk to. It wasn't comfortable, but at the same time it was very exciting, we were playing all these different places, and that took my mind off it."

Tensions aside, the bands generally stuck together, as all punks - not just The Slits - were under fire from the outside world most of the time. But the girls learnt how to handle situations quicker than most. "Whenever there was trouble it was usually The Slits that would save our arses," laughs Don. "They were like howling banshees, oh man..."

If the mood took them, of course, anyone could be a target for The Slits' aggression. On one occasion, Tessa let off steam at the Roxy club in the direction of Pistols drummer Paul Cook. Without rhyme or reason, the ‘quiet one' ran at him and ripped a hole in the back of his jacket. He'd stolen it from Malcolm McLaren that day though, so he must have anticipated at least some kind of karma.

Musically, The Slits were improving all the time; the cliche of how ‘they couldn't play' was already becoming a memory to those on the scene. Their rawness and exuberant musical innocence led them into experimenting in ways The Clash and Buzzcocks did not, and as a result of Palmolive's background they started to become curious about African music, which they would later explore in greater depth, and which certainly affected how Palmolive approached the drums. A tribalism was coming into play that would, even after she left the group, leave a stamp on The Slits that would be echoed in the notorious topless, muddy and defiant cover of Cut

The spirit of punk was supposedly all about trying something new, rejecting what went before, though admittedly most of the male groups still referenced the past whether they meant to or not. Those old, albeit very valid, influences of rockabilly, blues, mod culture and rock ‘n' roll still cast a retro shadow over the music of The Clash, Jonathan Richman & The Modern Lovers, The Lurkers and the Pistols - but The Slits didn't have those references simply because they hadn't paid them any attention. So they really did have to go a new way.

Palmolive laughs, "The public always seemed so amused by us, they were like, ‘I can't believe these girls are doing that!' There was definitely something about us because we were girls, and in some way we were also very naive. We were very raw, so that was not normal.

"The Clash were punk but they had that background, like Joe had The lOlers background, I didn't have that at all, none of us had. I grew up with flamenco music, I like African music, I had never really followed rock ‘n' roll. So even when I played the drums, I didn't like playing the hi-hat, or the cymbals like normal bands did, I liked the toms much better, so I'd always experiment with those sounds much more, I was curious.

"It was almost like when you give a little kid paint - it always comes out different because they don't have a preconceived idea about what they are supposed to do, and we didn't know. Some of it was an advantage and some of it was a disadvantage."

It was around this creatively charged period that The Slits started really thinking outside the box and experimenting on stage. Numbers such as ‘Vaseline' featured one section of the song with just voice and drums, the next section with drums and bass, the next with guitar and bass, then voice and guitar and so on. While they may have seemed chaotic, some of the original ideas they had clearly practised and thought about were executed truly effectively. As with art, it's easy for the ignorant to say, ‘My six-year-old could do that', but it's the idea that matters. And The Slits were full of ideas.

* A slightly different version of this story appears in Nils Stevenson's published diaries, Vacant, featuring Ari as the perpetrator of the jacket- ripping crime, but Tessa insists his memory clearly failed him on this anecdote. Credit where it's due.